People talk about sneakers as an investment. In some cases, sneakers are analogized to stocks or other financial instruments. On the surface, the mechanics of these two markets are pretty much the same – buy a sneaker, watch it increase in price, sell it. In reality, the sneaker game is much more akin to the drug trade.

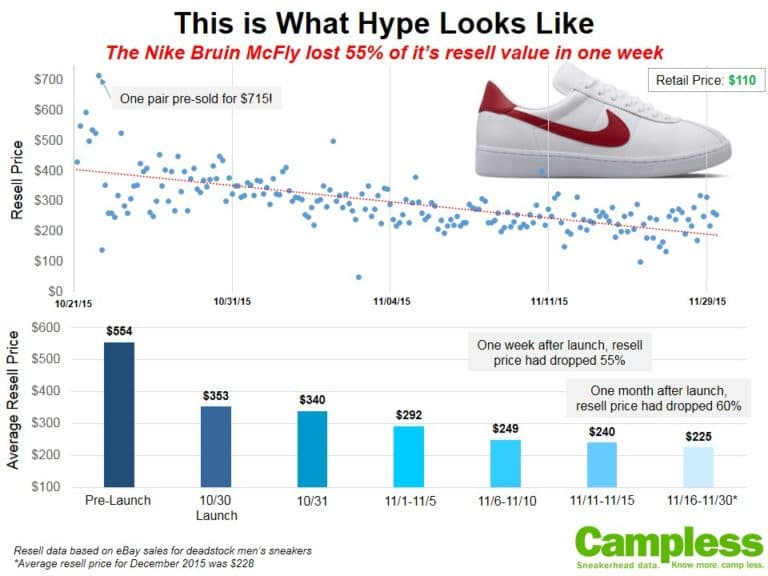

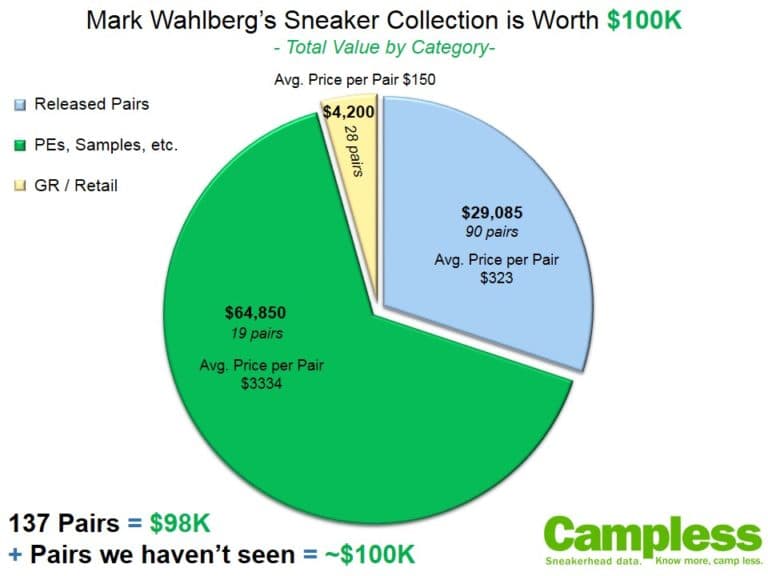

We were playing around with some financial visualizations of the “sneakers-as-a-stock” concept and created this:

The graphic is a little crude, but what you’re looking at is an Air Jordan 3 Black Cement (2011 release) tracked as an investment against the share prices of Apple, McDonald’s and the S&P 500 over the same 18 months. The net result is that if you had purchased a pair of J3 Black Cements for retail ($160) at release (11-25-11), and then sold them in May 2013 for the average price at the time ($266, according to our data), you would have made 82% on your money. Compare that to 17% for Apple, 14% for McDonald’s and 32% for the S&P, and sneakers sound like a pretty amazing financial asset.

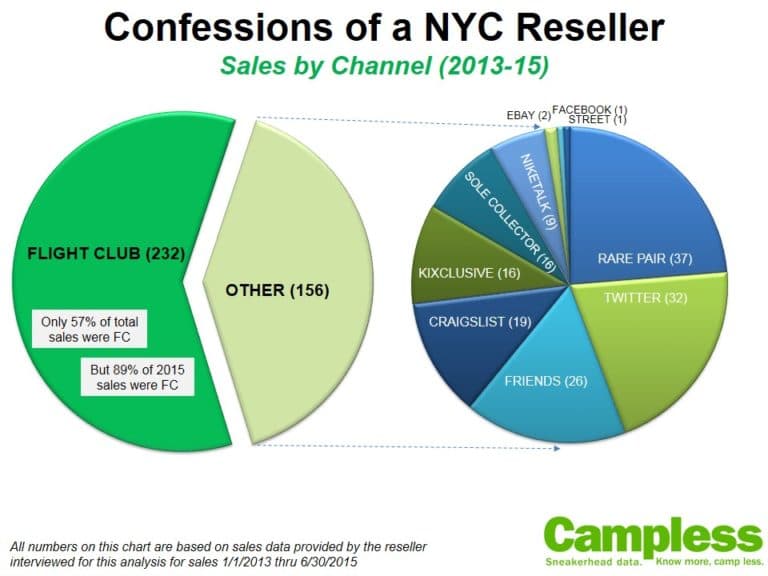

As we’ve seen all too closely over the past few years, this fake promise of true arbitrage is what drives resellers. There is no shortage of talking heads in the sneaker community with an opinion on resellers, so the only thing that we at Campless seek to add to that conversation is data analysis. No one can deny that resellers exist and play an integral role in our community, so perhaps we can help (for whatever your goal is), by analyzing the data and providing some insight.

Sneakers are not stocks

The above analysis assumes that sneakers are like stocks and that “returns” can be compared. There is one fundamental difference – one that you already know – which makes this untrue. Supply is limited.

The Black Cement comparison was intentionally written to induce an average person to conclude that Jordan’s are an amazing investment and we should load our portfolios with them. But the sneaker community understands that copping a pair at retail is the tricky part in the above example, particularly in large quantities. This is the seminal distinction from the stock market, which basically offers unlimited supply of publicly traded shares. And that is why this comparison is nothing more than an amusing exercise.

The sneaker resale market is an imperfect market. There is money to be made and people will find out how to do so, but there is a big difference between how it’s done in the sneaker market vs. the stock market.

In the stock market, those who make money are the ones who can repeatedly pick stocks or execute any number of complicated strategies, such as options, futures or short selling. In the sneaker market, however, those who make money are simply the ones who have access to supply (i.e., those who can cop at retail or less). And any sales strategy beyond choosing which online portal to use is almost certainly overkill, as there is virtually no risk of losing the retail-price investment.

Neither market is easy but there is almost no overlap in the skills needed to do each. So for all those resellers who fancy themselves as new age day traders, think again. The only scenario which is even close to this are the handful of true sneaker brokers: those buying at resell prices and either a) flipping for a profit due to superior negotiating skills; or b) sticking them in a closet and waiting years for appreciation due to decrease in supply. Either way, it’s a far cry from playing the market.

Sneakers are drugs

From a market dynamics perspective, the resell game is actually closer to the drug trade than the stock market.

Supply: Sneaker supply is limited and highly controlled. A “cartel” has an almost complete monopoly at the top of the supply chain, but there are always others vying for a piece of their action. At the other end of the spectrum, there is literally no regulation or barriers for anyone looking to enter the market. It’s easy to resell single quantities if you’ve bought too many, or even a few every now and then to support an individual habit. But there are very high barriers to gain access to large quantities in order to build a business.

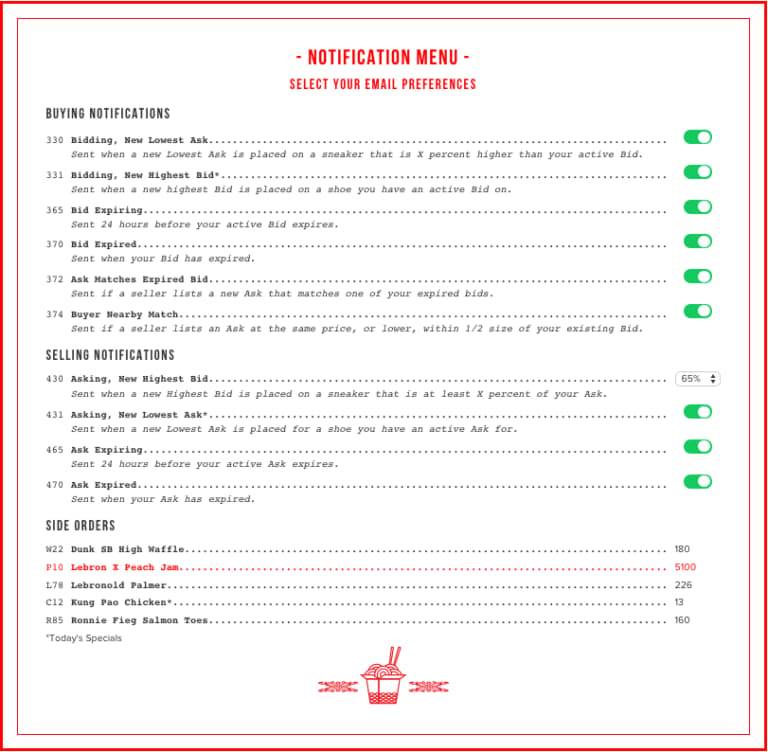

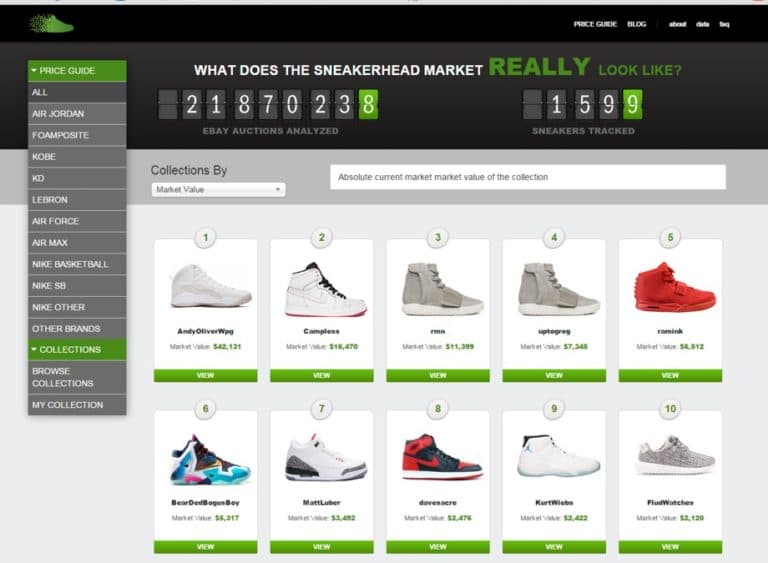

Pricing: There is no central pricing exchange (although the Campless Price Guide is trying to change that), but everyone has a pretty good ballpark idea of what something should cost.

Customers: “Addicted” buyers pay outrageous markups and dedicate their lives to the pursuit. There is nothing they cherish (or protect) more than a great “connect.” Quality, authenticity and purity are constant concerns for all involved. Sadly, there are even people killing each other.

Campless has no political agenda here, we’re just data scientists comparing the markets. But the similarities are striking. The sneaker business operates damn near identically to the drug trade.

But sneaker data is like stock data

That said, we’re still going to perform interesting analyses and create fun charts as if sneakers were stocks. Even though the two markets are fundamentally different, there are enough similarities in the data (such as price, volume, volatility and time) that we can create meaningful and interesting insights for the sneaker community. Besides, it’s not like we’re going to start tracking the market rate for weed (at least not publicly).

As always, here are some questions to ponder:

- Other than legality, are there any important market differences between sneaker resell and drugs?

- Besides the above, are there other ways the resell market is similar to the stock market?

- What other markets are analogous to sneakers?