Hardcoded in hip-hop’s DNA is an intense focus on time and time’s relationship to memory, history, and consumerism. From the start, hip-hop has positioned itself inside, and outside, of time, by borrowing and remixing anything and everything within reach. The very aesthetics of hip-hop interrogate notions of time and actively work to reshape how artists and audiences experience it. From iced out and bust down watches, conspicuous consumption, to posthumous performances, the experience of time and memory have always pushed hip-hop culture.

Of Time and Hip-Hop

In the promotional run-up to his monster album Astroworld, Travis Scott was photographed flexing two watches throughout 2018. Doubling down on the theme of time, Scott’s song “Watch” from the album features Scott, Lil Uzi Vert, and Kanye West ratcheting up their horological braggadocio. The chorus begins: “Look at your Rollie, look at my Rollie/That’s a small face, this a big face.” A year earlier, Cardi B took the rap world—not to mention our hearts—by storm with “Bodak Yellow” letting the world know that her “Rollie got charms, look like Frosted Flakes.” Scott reminded everyone that hip-hop was still very much all about big face watches, and Cardi let the world know that she was all about the finer things, the diamond-encrusted finer things.

Travis Scott and Cardi B showing off their watches.

Jewelry, massive chains, pendants, and luxury watches have always represented hip-hop’s performative grammar of wealth, luxury, and good old flexing. To get a sense of the stakes and stacks involved, look at any picture of top tier 80s’ rappers like Slick Rick, EPMD, Eric B. & Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, and LL Cool J. Ever since Run-DMC signed with adidas in 1986, hip-hop has continued to create, influence, and flaunt different fashion trends, both popular and exclusive. High-priced exclusive jewelry and accessories are nothing new in hip-hop.

[Clockwise L-R] Slick Rick, LL Cool J, Eric B. & Rakim

Since the late 1990s, luxury watches, followed by iced out watches and bust downs in the early 2000s and mid-2010s, have become de rigeur for many rappers. And if one bust down is nice, two, or three is even better.

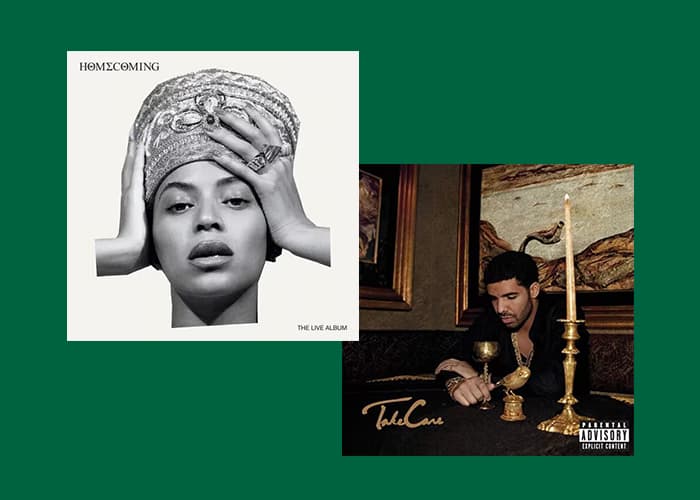

And since at least 2012, A-list rappers have been doubling-up the watches. In his video for “The Motto,” Drake rocks two Rolexes on his left hand. During the run-up to the release of his 2014 album, The Gold Album, Tyga was photographed wearing two gold Rolexes. Both former Young Money labelmates displayed a penchant for wearing more than one luxury timepiece at a time. However, any style or temporal transgression was muted because both men went for the plain jane Rolex look, and neither indulged in big face flexing. This was Drake and Tyga’s Norman Schwarzkopf moment. The general famously wore two watches during the 1990-91 Persian Gulf War, one set to Eastern Standard Time, and the other set to Saudia Arabian time.

Tyga, Drake, and General Norman Schwarzkopf (This is not the beginning of a joke.) The general rocked a Seiko SKX009 diver on his left wrist set to EST, and a Rolex Day-Date on the right set to Saudi Arabian time.

By 2016, however, big face, all-diamond everything reshaped the hip-hop watch landscape. Gucci Mane helped blow it out bigger and bolder, wearing three bust downs at a time on one wrist. Gucci’s wrist-stacking of expensive timepieces was not a new style choice, but the prominence of big face bust downs was something new. Along with this novel aesthetic presentation in hip-hop, there was a new inflection in the experience, meaning, and performance of time within hip-hop culture.

From Jacobs to Royal Oaks

Doubling and tripling luxury watches represent one facet of hip-hop’s contemporary play with time. Before the early 2010s’ fashion of rocking multiple watches, iced-out big face Jacobs, from Jacob the Jeweler, seeded the ground for the growth of bust downs.

In the early to mid-2000s, if you were a top-tier rapper, or had pretensions of becoming a top-tier rapper, you needed to get to New York and pay a call to Jacob Arabo, aka Jacob the Jeweller. He got his start working in Manhattan’s diamond district in the early 1980s but became Jacob the Jeweler by designing custom pieces for the hip-hop world in the early 1990s (Biggie is credited with being his first rap customer). In 2003, Jacob would design his first watch, which featured his love of all things bling, and hip-hop’s A-listers—from Jay-Z, Pharrell, to Kanye and Rick Ross—were all primed to buy.

Anthony “Geezy” Gonzales, the former manager of Clipse, provides a first-hand account of what it was like to shop for the famous multicolored Five Time Zone watch at the Jacob and Co. store. The watch is 47-millimeters wide and features five time zones on the face: New York, Tokyo, Paris, Los Angeles, and a time zone to be set by the wearer. Jacob offered the watch three different ways: the plain jane watch; the watch with an iced out bezel; and the total bust down. At first, Geezy picked the plain jane but soon decided he wanted to upgrade to the bust down. So Geezy went back to Jacob and applied his $30K plain jane as credit for the $125K watch. Time is expensive, but some time costs more.

A$AP Rocky and A$AP Ferg stunting with the Five Time Zone Jacob.

The other piece of this revolution in the fashion of (the) time was the size of the watch face. Diamond and jewel-encrusted pieces are legit, but if you failed to represent with that big face energy, then all the diamonds in the world couldn’t save your rep. Darrel Hasty, jeweler and brand ambassador of Hutch’s Jewelry in Detroit, also traces the timeline of iced out and bust down watches back to Jacob the Jeweler, as well as the advent of the oversized watch face. Beginning around 2005, Hasty says that “everybody wanted an iced out, 57-millimeter Jacob that looked like a dinner plate on your wrist with rainbow colors.” However, it would be another six years before the fully blown luxury watch would take hold.

Hasty and Geezy were emphatic that hip-hop time was different, and watches were a measure of that difference. Hasty says that hip-hop time is different on a bust down because once you start wearing a bust down, time does, in fact, change. According to Hasty, time is different because it’s all about trends. “Everything moves faster and faster, you see trends come in and out faster,” Hasty says, “you know what’s going on, and you know what’s coming before anyone else.” Geezy cosigns the fact that hip-hop time is different. and once you reach a certain level in hip-hop, time changes. “There’s a different sense of time, an elevated sense of time,” Geezy says, “you want to have a watch that reflects this. You’re not regimented; You’re doing things differently.”

And, of course, this is also all about status, distinction, and consumerism. Part of the appeal of spending five to six figures on a watch is showing off how much shine you can afford. “When you get a bust down, and you feel like your whole wrist is iced out, you’re just thinking that you’re on a whole other level that the average person will never know about.”

Whose Time is it?

Tricia Rose famously described hip-hop in terms of flow, layering, and rupture, and this is precisely how hip-hop and time function. Every time a break or sample is used in a song, it functions as these three modalities, going along with established practices and meaning, accumulating new sediments of context and history, and finally breaking with previously established time and meaning. Hip-hop can activate all three modalities simultaneously to effect a new sense of time and a new consciousness rooted in hip-hop culture.

Underneath the practicality is a history of imperialism as modernization imposed through time zones. From the late 1800s through the early 1900s, Western countries imposed the time zone throughout their empires, colonies and former colonies, all in the name of coordinating a global market made up of telegraphs, rail lines, and steamer ships, for the benefit of Western nations, in service of material, political, and temporal imperialism. Fast forward to the 1990-91 Persian Gulf War and the mix of oil, national sovereignty, military conflict, and coordinating a war halfway around the world, from the West to the Middle East, are all present in Schwarzkopf’s watches set to multiple time zones.

This is part of the context needed to understand hip-hop’s relationship with time. When Drake, Tyga, Offset, and Cardi B, stacked multiple watches on their wrists, they were flaunting their wealth as well as rupturing the longer history of global capitalism and its imperial underpinnings. First of all, to be able to own luxury watches indicates wealth and the ability to earn enough money within the flow of modern markets. Furthermore, seeing BIPOC succeed within a global economic system designed to exploit, extract resources from, and permanently impoverish these same communities helps to add layers of nuance and meaning-making on top of their success—this is where questions develop as to whether or not rappers are spending money “correctly.”

The rupture comes with the doubling (and tripling) of watches by rappers signifying that hip-hop has not only mastered earlier presentations and experiences of wealth foundational to white supremacist global capitalism but has been able to do so according to an altogether different conception of time. Hip-hop time moves in, out, and between the minutes and seconds of modern global capitalism so much so that multiple watches are needed to check the time: hip-hop time and global capitalist time. And the concept of an overarching, controlling tick-tock of ascribed time has become an owned decoration on a wrist. It’s an explicit harnessing of the impossible resource. It is wealth defined.

Layering the multiple meanings of hip-hop and time at play with multiple watches, the advent of big-face, iced out, and bust down watches continue to challenge notions of capitalist time. In addition to hastening temporal standardization by time zones, the industrial revolution also precipitated the rise of Fred W. Taylor and the scientific management of factory production. Taylor rose to fame in the late 1800s as one of the very first management consultants. His theories, known as Taylorism, sought to break down every step of industrial production into repetitive tasks such that every step was measured and timed for maximal efficiency. Under Taylorism, factory work became mind-numbingly repetitive and managed by the unceasing ticking of the clock. Diamond-encrusted watches are a horological riposte to time-management and efficiency. After all, these watches aren’t meant to tell time; they’re intended to dictate what time it is to others.

Further underscoring the temporal rupture at work with big face bust downs, Hasty admitted, “A lot of people who wear bust downs won’t even get the time set. I couldn’t even tell you how many guys I’ve sold bust downs to who could care less what time the watch says.” Setting the time becomes inconsequential. In terms of hip-hop time, and hip-hop time vis-a-vis capitalist regime time, it’s never going to be right anyway.

Throughout his 30-year-plus career with Public Enemy, Flavor Flav was one of hip-hop’s greatest hype men and the most conspicuous clock watcher in the game. Flavor Flav pioneered the big face look, wearing wall clocks as medallions. When asked about this, Flavor said, “I wear a clock because it represents time being the most important element in our life.”

“Time can’t afford to be wasted,” he continued, “We got to live each second to our best value.” Being mindful of the purpose and use of your own time is another way to fight back against systems of time management that values profit over humanity.

Buying and Selling Time

Hip-hop has provided a way for many black and brown artists to take back their time and control the course of their life and work. Hip-hop has also been heavily courted and appropriated by brands and corporations looking for a quick and easy way to seem cool, connected, even “woke.” This underscores the inherent tension running through the relationship between hip-hop and time: who exactly owns hip-hop time, and who is profiting from it.

This tension is manifest in the holographic resurrection of Tupac Shakur. During his brief life and career, he was a voice of dissent and rebellion within and without popular culture. Most of his records and biggest hits involved notions of time: never having enough time (“Death Around the Corner”); time as a burden (“Changes”); time and memory (“How Long Will They Mourn Me?”). In addition to the music he released during his career, Tupac has had a long afterlife with a string of posthumous releases. Nothing illustrates his timeless longevity more than the Tupac Hologram.

Snoop Dogg and Hologram Tupac performing at the 2012 Coachella festival.

Conceived by Dr. Dre for his 2012 Coachella festival set, the virtual Tupac performed “Hail Mary” and traded verses with Snoop Dogg on “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted.” For nearly ten minutes, a digitally resurrected ‘Pac performed and tangled hip-hop notions of time, history, and commerce. Careering from high pomp to high camp, hologram Tupac initially threatened to invalidate the work and impact of such a brief and blazing career, all in the service of a bizarre and rapacious stunt.

Held within the hologram, however, was the opportunity to reconnect the performer, his art, and collective grief. For artists and communities intentionally marginalized by institutions of time and power, the Tupac hologram offered the potential to escape and transgress the imposed order. Because of hip-hop’s fugitive relationship with time, history, and consumerism, a Tupac hologram still functioned as a transgressive symbol of hip-hop authenticity on the Coachella stage in a way that hologram Elvis performances would only ever function as nostalgia and sad spectacle.

All of these tangled notions of time, memory, and consumerism served as the basis for Supreme’s SS20 Tupac collab. Instead of introducing a range of t-shirts and skate decks featuring anything from the life of Tupac, Supreme used hologram Tupac, complete with Supreme boxer briefs, for the collab. Like DJs extending breaks or horologists not bothering to set the time on a bust down, Supreme’s Tupac collab should be read as an attempt to extend and resurface the impact of Tupac Shakur, combined with some classically irreverent streetwear marketing; both signifying on time, memory, and markets. Whether on stage at Coachella, or hyping Supreme’s latest collab, the broader convolutions of hip-hop and time open spaces for experiences beyond buying and selling.

The relationship between hip-hop and time has created a productive, imaginative tension that is evident across music, fashion, and commerce. Through an over-the-top aesthetic that celebrates wealth and conspicuous consumption, hip-hop simultaneously offers an embrace and rejection of temporal regimes that coordinate the global network of capitalist expropriation. And like some hip-hop Proustian vision, lost time and lost community can be recaptured and celebrated in the marketplace, too.