Hip-hop’s introduction to France was about as hip-hop as anyone could imagine. In November 1982, a sizable contingent of hip-hop’s first wave of stars landed at Orly Airport in Paris for hip-hop’s first international tour, the New York City Rap Tour. After straggling out of the airport to the tour bus, Fab 5 Freddy, FUTURA 2000, and Dondi White decided to customize their Europe 1 corporate tour bus. Fab and company announced their arrival in Paris by tagging the bus, which would effectively roll throughout France, announcing hip-hop’s appearance during the tour, setting the stage for hip-hop to become a global culture.

Fab and the other New Yorkers brought hip-hop to France, but French adopters helped codify the who, what, and where of the hip-hop nation. The quick adoption and adaption of hip-hop in France are based on authentic cross-cultural relationships founded on community, music, and style. As French hip-hop matured, its unique culture was based on an official history it helped create, further reinforcing the official story of hip-hop from both sides of the Atlantic. By the early 2000s, closing an almost 40-year loop of cultural collaboration and exchange, French culture and fashion would return the favor and begin to influence American hip-hop.

Paris to New York

The multiple personal and professional connections between French and New York hip-hop cultures began in the early 1980s in downtown Manhattan. Two French nationals, Bernard Zekri and Jean Karakos, settled in New York and became captivated by hip-hop culture. Zekri and Karakos were both involved in writing about, producing, and selling music. In typical Gallic fashion, and since both men worked in the French media and music industry, they decided they could help bring this captivating new culture to France. For Zekri, “hip-hop culture announced an art of recycling, recovery, mixing, copy-pasting, all these things we would be doing with the internet, an iconoclastic form of plundering,” and he wanted a part of the action.

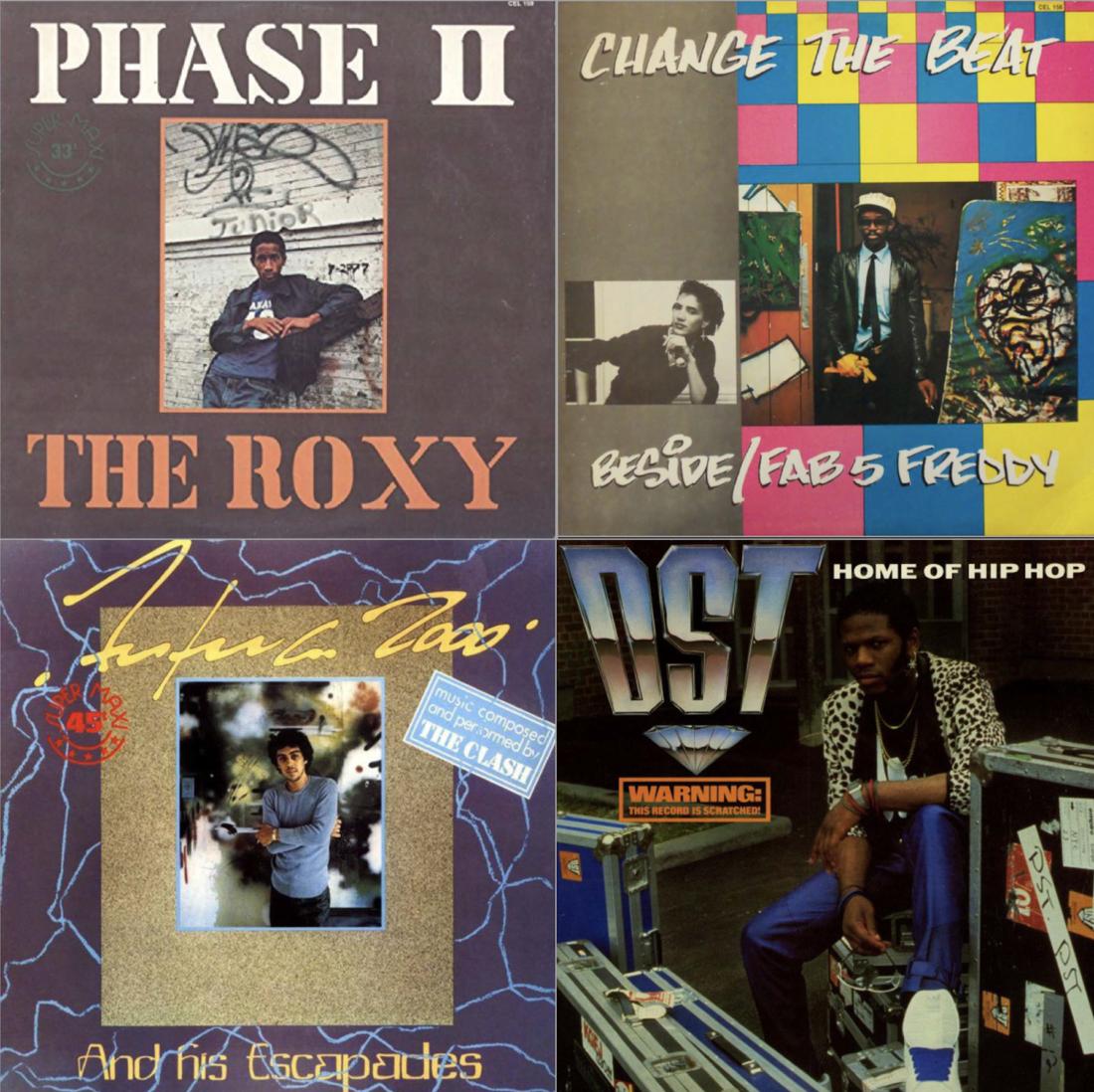

Bernard Zekri arrived in New York in 1980, initially working at a restaurant, the Wine Bar, in the East Village, and then writing for the French magazine Actuel. He would spend his nights bouncing between downtown clubs like Danceteria, Club Negril, and the Roxy, all of which were frequented by b-boys and b-girls. Zekri befriended Afrika Bambaataa and earned an official “Bronx Pass” from the Zulu Nation founder, ostensibly giving Zekri free reign to travel throughout hip-hop’s home borough. In September 1980, Jean Karakos, head of the Paris-based label BYG, decamped to New York, where he met Zekri and founded Celluloid Records. This relationship would provide recording opportunities for New York hip-hop pioneers, including FUTURA, Grandmixer D.ST., PHASE II, and Fab 5 Freddy, among others. The links established between Zekri, Karakos, and a roster of Bronx-based hip-hop pioneers would lead to hip-hop’s first international tour.

Celluloid Records' releases clockwise from upper left: PHASE II, "The Roxy," (1982); Fab 5 Freddy and Beside, "Change the Beat," (1982); Grandmixer D.ST., "The Home of Hip Hop," (1985); Futura 2000, "The Escapades of Futura 2000," (1982).

The New York City Rap Tour

The connection of Bronx hip-hop pioneers, the downtown Roxy nightclub, and Zekri and Karakos cohered into hip-hop’s first international tour, The New York City Rap Tour, in November 1982. For two weeks, the tour brought Zekri and Karakos back to their native France, performing in ten French cities, as well as two shows in London. David Hershkovits, who chronicled the tour for the Sunday News in 1982, described it as a success in cross-cultural communication, writing that the “audience starts to dance and in a few minutes borders melt in the heat of the soul-sonic blast.”

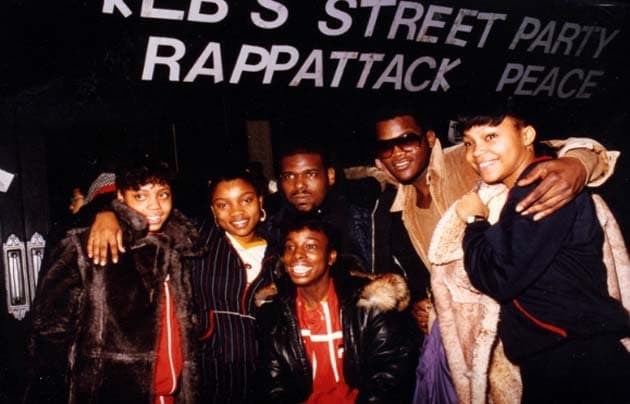

The Double Dutch Girls (front) with Afrika Bambaata (back, center) and Grandmixer D.ST. (back, left) in France during the tour (1982) // dailyrapfacts.com

Planting hip-hop culture in France was the main purpose of the tour according to Roxy founder and New York City Rap Tour co-producer Kool Lady Blue. She said, “the whole idea is to get everyone dancing. It’s not a band we’re bringing over. We don’t want people to stand and watch. We want people to participate. It’s a party thing, not a gig.” When Kool Lady Blue mentioned dancing and participation, she was referencing the type of inclusive dancing that took place at The Roxy, that included full breaking routines to spontaneous moves. As a result, the line between audience members and performers was never fixed and was easily breached throughout the tour. The porousness between fixed roles of performer and observer during the tour provided French audiences the opportunity to turn US hip-hop into local acts of culture, whether through actual participation or acts of imagination.

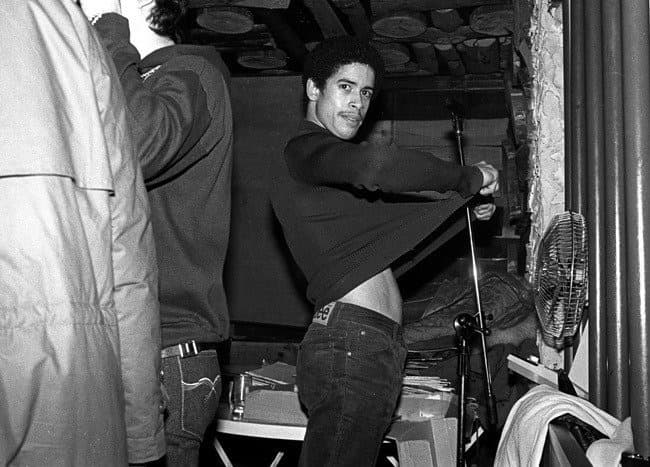

A classic night at The Roxy, New York (1982) // hiphopphotomuseum.com

During the tour, legendary b-boy Crazy Legs of the Rock Steady Crew recalled one interaction: “this dude comes up to me and says he wants to go to New York to learn to do breaking in school. And I tell him we make it up, and he don’t believe me.” The subtext of this interaction was Crazy Legs’ implied direction for the audience member to go out and create his own version of breaking, and by extension hip-hop culture. In one brief interaction, repeated again and again throughout the tour, Crazy Legs, and his fellow tour members, were able to communicate hip-hop’s cultural program of self-representation, giving everyone license to shape hip-hop culture in any way that was personally and culturally authentic. As hip-hop was increasingly subsumed by rap music in the US, France championed and promoted breaking and all forms of urban dancing as “le hip-hop.” Ironically, France kept the spirit of hip-hop’s cultural elements of self-representation alive even as they were neglected throughout the 1980s and 1990s in the US.

Crazy Legs cooling off backstage during one of the New York City Rap Tour shows (1982) // dailyrapfacts.com

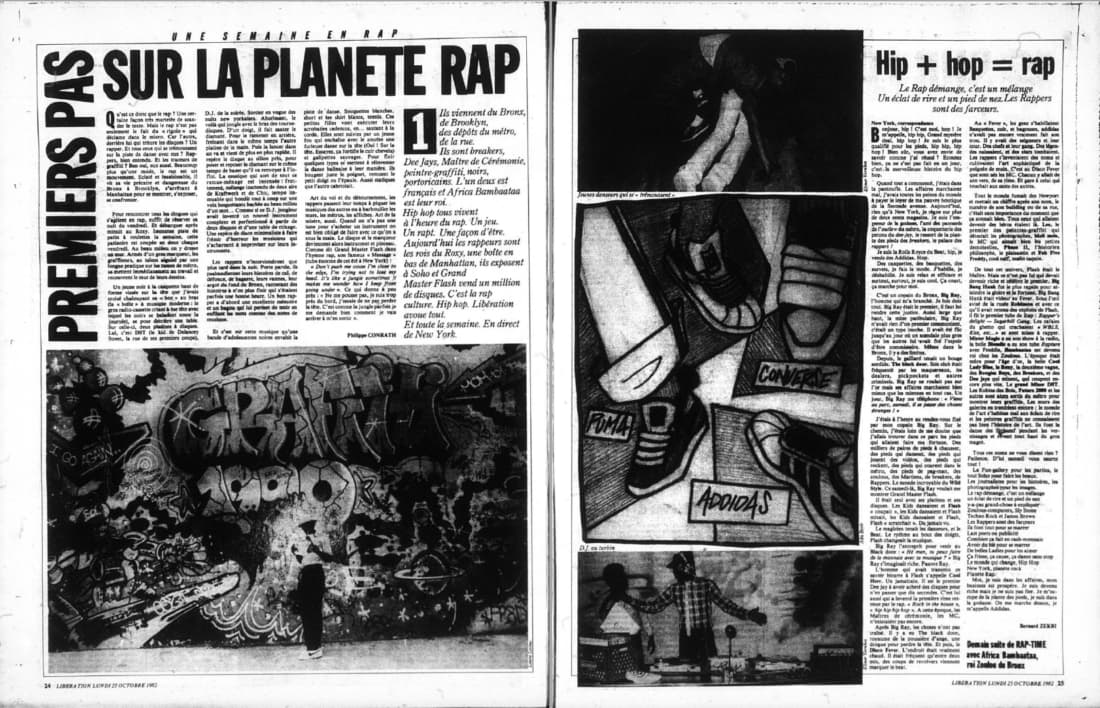

Prior to the tour, Zekri wrote the bulk of a series of articles explaining hip-hop culture and profiling some of the main originators in a series of articles for the French newspaper, La Liberation. Running October 24-31, 1982, the “Week in Rap” provided the social, cultural, and historical context for the newspaper’s audience to understand the upcoming tour. La Liberation’s “Week in Rap” provided a French audience with a primer on hip-hop culture, while also establishing the limits of what constituted hip-hop culture.

Day one of the "Week in Rap" published in La Liberation, October 25, 1982 // author's personal archive

The tour de force article from La Liberation’s series connected the importance of consumer goods, place, and culture creation as fundamental to hip-hop expression. Zekri gave a walking tour of the world of hip-hop from the Bronx to downtown Manhattan, from the perspective of a pair of sneakers worn by a fictional NYC resident, “Big Ray.” Zekri concluded the article with his anthropomorphic narrator revealing that, “My name is Addidas [sic].” Zekri wrote from the perspective of a pair of adidas sneakers because he was authentically interested and invested in hip-hop culture. Zekri recognized that shell toe adidas were a part of hip-hop fashion and function because he went to jams and clubs and immersed himself in the culture. Cementing Zekri’s bona fides, his article was published almost four years before Run-DMC’s famous “My Adidas” was released.

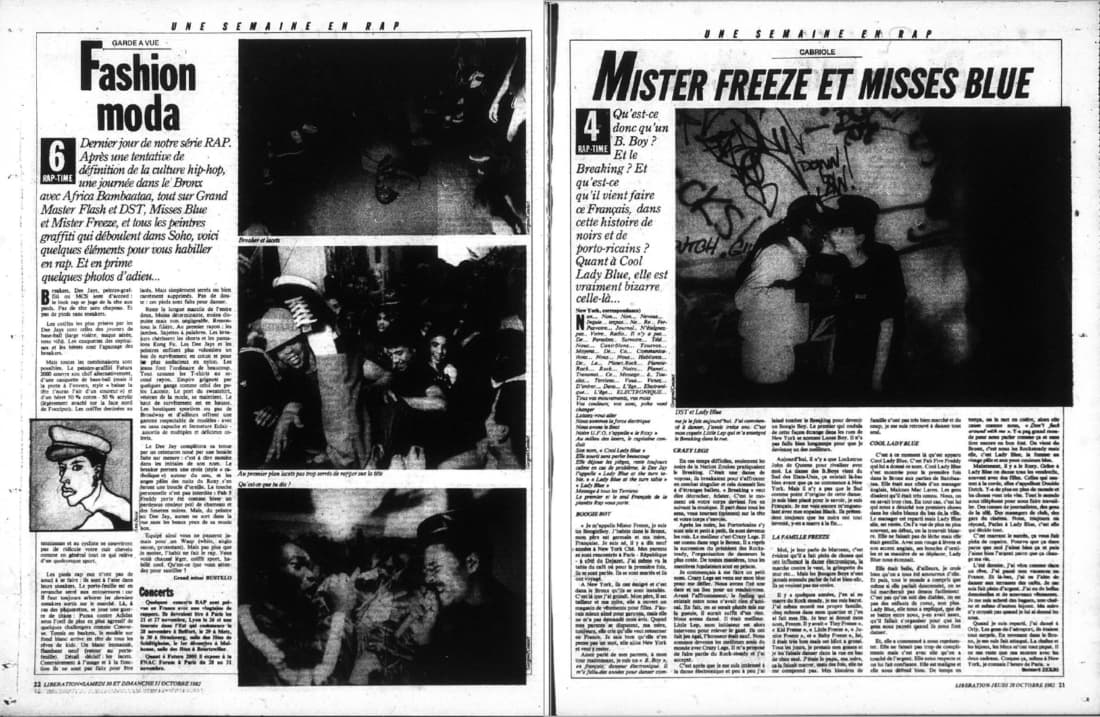

For the series’ final article, “Fashion Moda,” the writer Bustelo Thibaudat examined hip-hop fashion presenting the “clothes needed for rap fashion.” Bustelo described the centrality of fashion and style to hip-hop, presenting hip-hop as a total form of cultural expression that also included fashion. Of course, sneakers received the bulk of the article’s attention. In addition to choosing between various sneaker brands, Bustelo explained, the hip-hop devotee needed to determine whether or not to represent with tennis or basketball shoes. And, furthering the sartorial synopsis, readers were told that the sneaker brand and silhouette was not enough; the “decisive detail” of the early 1980s’ sneaker fashion was the laces. The brand and silhouette determined whether or not laces were intricately tied or completely removed. No matter the sneaker preference, Bustelo confided in his readers that “all the shoes were meant for dancing.”

(Left) "Fashion Moda," La Liberation October 30-31, 1982; (Right) "Mister Freeze et Misses Blue," October 28, 1982 // author's personal archive

“Fashion Moda” even created the newspaper version of the ubiquitous fit pic, based on form and function. After deciding on sneakers, styles of pants were recommended based on your hip-ho activity: shorts and kung fu pants for breakers, and cotton or nylon sweatpants for DJs and graffiti writers. Then, to top it all off, the next choice to be made was whether or not to wear a Lacoste polo shirt with a sweatshirt or a tracksuit. Although the choice of sweatshirt or tracksuit could be a daunting decision, the article informed readers that “sport stores along Broadway and elsewhere offer a range of brands—with or without hoods and zippers—in multiple colors.” French readers received a crash course in hip-hop fashion, with an easy to follow guide for how to replicate it themselves. It would be two more decades when the favor was returned and French fashion would inform the style of American rap stars.

Sidney Duteil and H.I.P.H.O.P.

The son of a jazz musician father and mother who immigrated to France from the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, Sidney Duteil became the most important person to turn France on to hip-hop. Like so much else in hip-hop, it all came down to the beat.

Throughout the 1970s, Duteil honed his DJing skills at clubs and bars throughout Paris including the Rocco Club. He would branch out to other clubs after the Rocco Club’s manager refused to invest in another turntable, limiting what he’d be able to do. His next gig, DJing at a Franco-American club in Montparnasse, La Boheme, specialized in soul and funk 45s for the largely American clientele. His time at La Boheme gave him the musical knowledge of so many of the samples and breakbeats the first generation of hip-hop DJs would use to create the genre. By 1980, Duteil was DJing at L’Emaraude Club, and one of two or three other DJs in Paris, and all of France, that used two turntables to extend the breaks of songs to create something wholly new, hip-hop. So by the time the New York City Rap Tour arrived in 1982, Duteil was ready to help push hip-hop further into French cultural life.

Following the tour, Duteil would go on to host H.I.P.H.O.P. the first French television show devoted to hip-hop culture. Premiering in 1984, the show aired weekly for over a year. Duteil’s program featured a variety of French and American musical artists and performances, and breaking, and a variety of audience participation and instruction in hip-hop culture. By the time the show ended in 1985, Duteil’s program had provided an authentic template for French youth from all across France to create their own brand of hip-hop expression.

Sidney Duteil (1984) // Sophie Bramly, ushistoryscene.com

From the very first episode of the series, Duteil educated his audience on what hip-hop looked like, sounded like, and the communities and neighborhoods hip-hop called home. Each H.I.P.H.O.P. episode was fifteen minutes long, consisting of three segments: an introductory interview segment with a notable guest, a segment called “La Leçon” (The Lesson), followed by “Le Défi” (The Challenge).

FUTURA interviewed by Sidney Duteil, H.I.P.H.O.P. episode 4 (1984) // author's personal archvie

“La Leçon” featured Sidney and some French b-boys providing a lesson in hip-hop culture. Usually, these segments were dedicated to dance, but also offered tutorials on how to rap, DJ, and dress appropriately.

"La Lecon" title card, H.I.P.H.O.P. episode 5 (1984) // author's personal archive

The third segment, “Le Défi,” the history of competition and battling in hip-hop culture. Each challenge featured two young contestants hailing from a cross-section of Paris neighborhoods and suburbs and who were racially and ethnically diverse. Importantly, each contestant dressed like a prototypical 1980s b-boy, complete with sneakers, sweatpants or track pants, and a polo shirt or sweatshirt. Cementing the connection between fashion, hip-hop, and consumer goods, the winner of “Le Défi” always walked away with a name brand outfit including adidas sneakers and a tracksuit or sweatsuit from a range of popular brands like Reebok and Champion.

"Le Defi" title card, H.I.P.H.O.P. episode 4 (1984) // author's personal archive

H.I.P.H.O.P. also served as a way to maintain personal relationships forged between record producers and artists in New York and Paris. Just about every performer and guest of the show had forged international relationships connecting the Bronx, downtown Manhattan, and Paris. Many of the guests had a formal relationship with Celluloid Records, and the label’s French brain trust: Bernard Zekri and Jean Karakos. Not surprisingly, most of these artists were featured on H.I.P.H.O.P.

Place is the Space

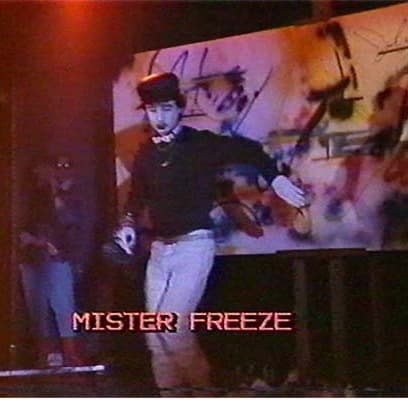

The cultural exchanges, resonances, and quick adoption in practice and in the media in France following the New York City Rap Tour would not have been possible without a similar material, cultural, and spatial foundation in both Paris and New York. Ringing the outer edges of Paris, the public housing developments—les banlieues—functioned similarly to public housing throughout the Bronx and New York, places increasingly used to segregate according to race and class and where American hip-hop flourished. During the tour, Mr. Freeze, the Bronx-raised, French-born b-boy advised the other tour members: “Police here, they can shoot at you if you don’t stop when they call.” The underlying message of Mr. Freeze’s warning connected the experiences of the predominantly non-white New York youth who grew up with the threat of state-sanctioned violence with the predominately non-white and immigrant populations of the Parisian banlieues.

Mister Freeze performing during the New York City Rap Tour (1982). He would often perform in mime's makeup because he beleived that mimeing and the work of Marcel Marceau were directly related to breaking // dailyrapfacts.com

Representing the cultural heart of hip-hop, Afrika Bambaataa and his Zulu Nation were able to influence French hip-hop through a shared understanding of life lived on the social, political, and geographical margins of society. Bambaataa founded the Zulu Nation from the Bronx River Houses housing development in the Bronx in 1973. Bambaataa’s goal was to organize the various youth cultures of the poor and working class communities that made up hip-hop under the banner of the Zulu Nation. Part cheerleader, part cultural historian, and part enforcer, Bambaataa and the Mighty Zulu Nation initially promoted hip-hop as first and foremost grounded in place. As part of the 1982 tour, Bambaataa was able to make connections and plant seeds based on cultural and geographical affinities between the projects and les banlieues.

Two years after the tour, Afrika Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation officially started a new chapter in Paris. In 1984, French hip-hop pioneer DJ Dee Nasty would become the Grand Master of Zulu Nation France and would go on to release the first French hip-hop album, Paname City Rappin’. Dee Nasty would nurture and produce the next wave of French hip-hop including the groups Les Little and Assassin whose content was thematically similar to Zulu Nation’s hip-hop proselytizing connecting knowledge of hip-hop history and geography with cultural creation. Each of these groups and artists understood and represented themselves through hip-hop culture, as well as representing life in les banlieues, continuing to provide a creative template for the next wave of French hip-hop.

Fashion Reigns Supreme

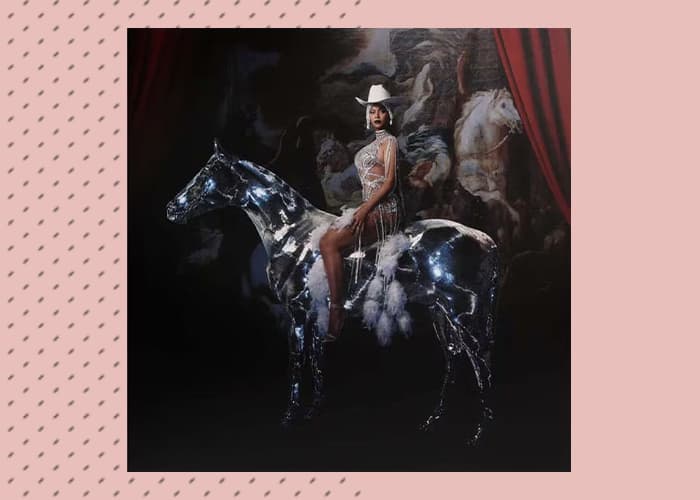

Hip-hop has always focused on fashion, and fashion has always found inspiration (and appropriation) from hip-hop. From the Dapper Dan and ‘Lo Life ‘80s, Phat Farm and FUBU ‘90s, to the rise of the hip-hop cognoscenti frequenting runway shows and the collapsing boundaries between streetwear and luxury. A half-century later, we’re still celebrating Biggie in BAPE [link to hip-hop japan], Raekwon on the catwalk for Tommy Hilfiger, and Tupac walking the runway for Versace in Milan, while all their cultural descendants are inextricably woven into current fashion movements.

Since fashion and style are such an integral part of hip-hop culture, it only makes sense that American hip-hop culture and its stars still make their way to Paris and France. Historically, France has served a much more forgiving and inclusive country for black people, particularly black artists, than Jim Crow America and the continuing scourge of white supremacy following the civil rights era. But the terms of engagement are different, especially for famous American rap stars. Once upon a time, black artists would seek freedom and relative anonymity in an expatriate milieu. These days, a visit to France represents a very public flex of wealth, sophistication, and style.

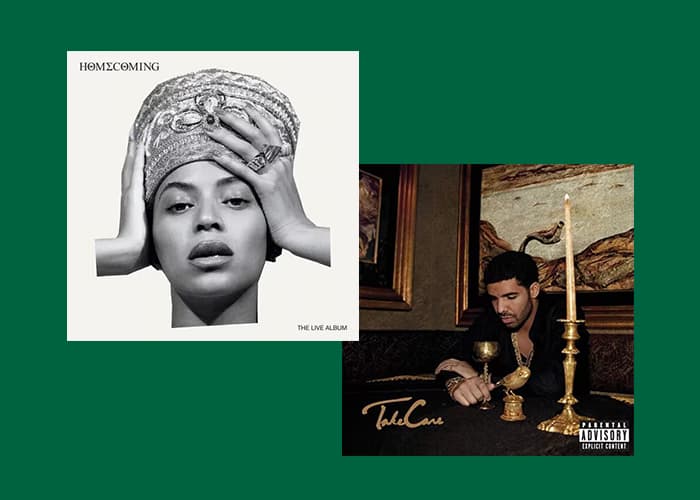

American hip-hop’s foray into the high fashion world would begin in earnest in the 1990s with hip-hop fashion lines such as Wu Wear and Diddy’s Sean John line, and by the early 2000s Jay-Z, Diddy, and Kanye West were runway show regulars. Even Diddy won the 2004 CFDA for his work with Sean John. By the 2010s, hip-hop and high fashion became reciprocal cultural partners, drawing inspiration from each other. Of course, Kanye and his collaborators have come to symbolize hip-hop and high fashion’s synthesis; of course we can trace this emergence in part to France and Paris.

Before Jay-Z and Kanye West dropped one of the hardest and most incendiary records about transatlantic ballin’ with “Niggas in Paris,” Kanye had made an important pilgrimage to Paris Fashion Week. In 2009, Kanye, Virgil Abloh, Don C, Taz Arnold, Chris Julian, and Fonsworth Bentley descended on Paris Fashion Week like bespoke prophets returned from some future fashion age. Photographer Tommy Ton took the iconic group shot and posted it to his blog, shifting the center of the hip-hop fashion universe from the US to Paris. Considering this photo from the vantage point of a decade later, this truly was a vision of the future. Each man in the photo, in his own way, has helped connect the worlds of hip-hop, streetwear, and high fashion.

(Left to Right) Don C, Taz Arnold, Chris Julian, Kanye West, Fonzworth Bentley, and Virgil Abloh, Paris (2009) // Tommy Ton, nicekicks.com

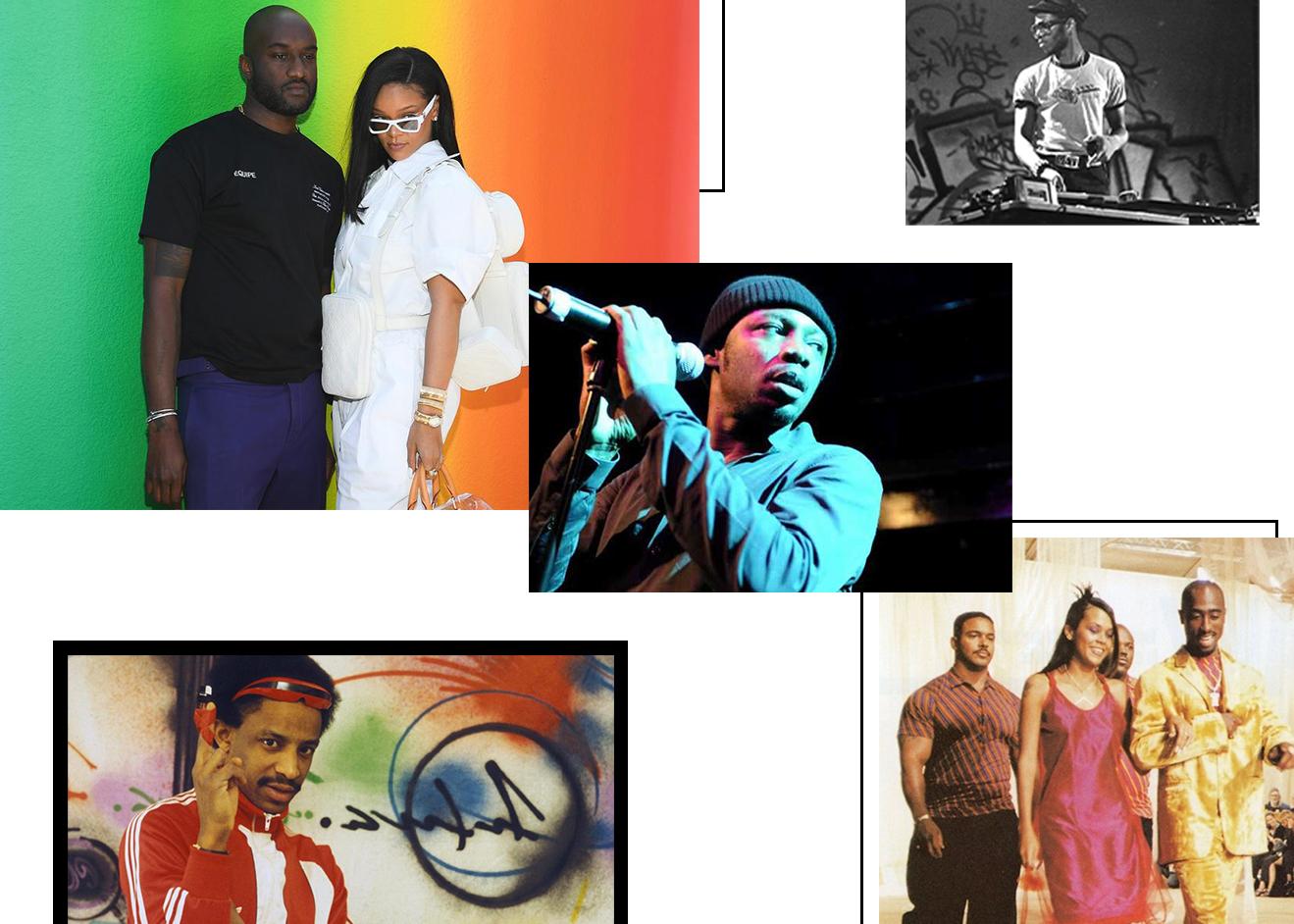

Besides Kanye, Abloh has undoubtedly had the most influence on hip-hop’s ascendance over the creative direction of streetwear and high fashion. Yes, A$AP Rocky, Tyler, The Creator, and many more are key figures, but Abloh is clearly the king. In 2018, Abloh debuted his first collection as Louis Vuitton’s menswear artistic director at the Jardin du Palais Royal during Paris Fashion Week. Abloh’s appointment to Louis Vuitton was not without controversy, but it signalled hip-hop and streetwear’s legitimacy in the world of high fashion. Many of the models walking the runaway included Abloh’s hip-hop friends including Kid Cudi, Theophilus London, Playboi Carti, the French-British rapper Octavian, and A$AP Nast. Abloh’s show wasn’t the first time rappers roamed the catwalk, but this did represent the first time that a major luxury brand’s show was designed and executed wholly from an authentic hip-hop informed perspective. For his Off-White label’s 2020 Paris Fashion Week Show, Abloh unveiled his newest Off-White x Nike Air Jordan 5 prior the sneakers official release proving that Paris continues to be center of the fashion world, and center of the hip-hop and luxury world, too.

Virgil Abloh's first LV show, Paris (2018) // Getty Images

Le Hip-Hop Aujourd’hui

Since 1982, French hip-hop has been developing its own forms of expression and content. By the late 1990s, French hip-hop was adding its voice to hip-hop’s global dialogue and impacted popular culture. Perhaps the most important figure in French hip-hop is MC Solaar. Solaar’s first single, “Bouge de là” (Get out of here), went platinum at the same time he opened up for De La Soul in Paris in September 1991. He would go on to record with Missy Elliott and Guru of legendary hip-hop group Gang Starr. But he is most recognizable for his 2001 song “La Belle et Le Bad Boy” (The Beauty and the Bad Boy), that used on the final episode of Sex and the City, in addition to episodes of The Hills, and True Blood. Solaar’s influence has reverberated through both French and American hip-hop with will.i.am stating he prefers Solaar over Tupac.

MC Solaar // independent.co.uk

The current generation of French hip-hop artists continues to evolve the look and sound of the culture, following the example of figures like Solaar, and the initial cross-cultural interaction established during the 1982 New York Hip-Hop Tour that continues to the present day. Each of these French MCs combine a unique singular style with a foundation in the places and experiences of their lives.

Gambi

Hailing from the Paris suburb Fontenay-sous-Bois, Gambi is one of France’s rising hip-hop stars. Within Fontenay-sous-Bois, he grew up in the La Redoute neighborhood of Val-de-Marne. La Redoute resembles the campus of a New York City housing development, with several buildings gathered around a central, concrete commons area. Several of his videos, including “Popopop,” have been filmed in his neighborhood. Just last year, Gambi became the face of the French brand Afterhomework for Paris Fashion Week.

Lorenzo

Jeremie Serrandour, aka Lorenzo, grew up in Brest, in the far northwest of France. He’s one half of the duo Columbine, and he’s a troll rapper with some serious bars. What is so compelling about Lorenzo beyond his music is his outré sense of style and knowledge of American and French hip-hop history. His 2019 album, Sex and the City, is an obvious allusion to MC Solaar and the HBO series. The lead single from his album is the straight-up banger “Nique la BAC” (Fuck the Anti-Crime Brigade), a spiritual companion to NWA’s seminal “Fuck tha Police” from 31 years ago.

Heuss l’Enfoire

Following French President Jacques Chirac’s failed 1996 “Marshall Plan for les banlieues,” the public housing developments increasingly became home to African and Arab immigrants. Coupled with France’s political turn to the right over the last quarter century, les banlieues have become increasingly stigmatized. For Karim Djeriou, better known as the Algerian-French rapper Heuss l’Enfoirė (Heuss the Jerk), this is the France he knows. Growing up in the La Sabliere section of the Paris suburb Villeneuve-la-Garenne, Heuss’ persona is cocky, brash, and ego-centric. He continues hip-hop’s long established braggadocio posture. His most recent hit, “Khapta” (Arabic for “drunk”) is over the top club rap extolling the virtues of excess.

Hip-hop culture’s endurance is the result of the global relationship between the US and France. The legacy of hip-hop’s first international tour throughout France is one of missionary work and the recognition of cultural cousins. Because so much was similar, from the media and music industries, a love of fashion, and similar places of designed neglect, hip-hop was a common language that could be easily transmitted and received. France represents the second major hip-hop market besides the US, and the 21st century history of French fashion and style influencing American hip-hop stars and culture demonstrates this longstanding cultural collaboration has become a partnership between equals.