“No Curator” focuses on the most important and cutting edge visual artists who create and draw inspiration from the interconnected cultures of StockX. In this installment of “No Curator,” artist Tyrrell Winston discusses how his exposure to art throughout his childhood and well into his adulthood has inspired him to be the artist he is today. Winston also discusses the influence of sports, skate culture, modern art, and much more.

See more from Tyrrell Winston on his website and Instagram and inside the galleries Library Street Collective (USA) and Stems Gallery (EU), where you can find some of his work.

The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

StockX: Would you please introduce yourself?

I am Tyrrell Winston, and I’m an artist based in New York City.

How did your childhood influence your art?

I grew up in Southern California; I’m from Orange County, California. My mom is an artist and illustrated children’s books and had her own business, and my dad’s a pastor, so it’s not exactly a traditional upbringing. My parents both pursued things that they were very passionate about. And that’s maybe the biggest reason I think that I am an artist—because I didn’t have parents who had a traditional nine to five. They always said, “Pursue what you’re passionate about. We’re going to support that,” and they have always encouraged me to do that. That and growing up in Orange County in the early nineties meant skateboarding and playing basketball, that was my childhood in a working-class neighborhood.

Installation view of Encore, photography by Tim Johnson courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective

Do you feel that having parents with careers they were passionate about has something to do with you choosing a job that you are passionate about?

It just came to me on my own. I mean, growing up, I kind of thought it was ridiculous, and I thought, “Why don’t my mom and dad have normal jobs, like my other friends’ parents?” And now I see how cool that is and what that just enabled me to think about. Of course, I didn’t realize that while it was happening. It is now, later in life, that I’m able to appreciate that.

Besides your parents, do you have any memories from childhood that pointed toward your future in art?

I can’t think of anything. There wasn’t a moment in my childhood that looked like I was going to do art. I didn’t decide that until later in life after college. I mean, the memories I have are skateboarding, throwing water balloons at cars, things like that.

Can you describe your first encounter with art?

Well, the first moving experience I had with art was—I might get the year wrong—between 2006 and 2007, I think. I went to MoMA, and I saw this Dadaist exhibition. I spent a few hours going through the exhibition and re-walking it. And I didn’t go to art school, I don’t have a background in art history, but this was work that really spoke to me. I felt a way I’d never felt seeing art; I didn’t feel intimidated by it. And I wanted to investigate that more. So this Dadaist retrospective was a very seminal moment for me discovering art and developing my very early taste. I realized that I do like this, and I want to make things that can add to or have some context with this.

Was that when you decided to be an artist?

I was 21-22 ish when I said, “Okay, I think I want to do something in the arts.” I didn’t know that I necessarily wanted to be an artist.

When did you truly begin to dedicate your efforts to art?

Let’s see; it would have been in 2012. So I’d been out of college. I graduated from college in 2008, and I bounced around from a few different jobs. I was doing graphic design and art direction, and I was just spending more and more time making art, and it was at that time that I said to myself, “I’ve got to just do this. I got to figure out a way to make it happen.”

Basketball and streetwear culture represent an essential motif in your work. What role does basketball play in your life, and how did that translate to your artwork?

Well, the sport of basketball is the work that I’ve become known for most. But I’m looking at sport as a medium, and when you look at sports and art, now there’s a little more crossover. But typically in Western culture, there are two, the left and right side of the brain. You have a quarterback who excels in art, and people say, “Don’t do art.” but I think you can do both. And I like this idea of taking something like sport, it’s very brutish, but elevating it in a way where it’s still about sport, but it’s not about sport.

So much of my work is about embedded history. All the basketballs that I use are all used, and I want people to focus on the story. Did someone give up on something? Did someone keep going? Some of those balls are so well-loved that they don’t even look like a ball. I think it’s an exciting way of using sport to help people recognize art that maybe they wouldn’t typically look at it. At the same time, my work is rooted in art history, and I want it to be able to exist in both of those worlds. But when I started making work and viewing art, it was so intimidating because I didn’t know if I was even allowed to be in the gallery. I felt like: I don’t know this, I don’t know that, whatever. So if my work can invite people in a way that they wouldn’t necessarily interact with art, then I’m totally open to that. And I like that.

Installation view of Encore, photography by Tim Johnson courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective

Did you have any family or friends that were interested in sneakers or basketball as you were growing up that influenced your taste and style, or was it all something you developed on your own?

It’s a combination of both. I remember growing up, and my grandfather would always wear [Reebok] Club Cs, and I always thought they were cool, and they were kind of grandpa’s shoes. But grandpa’s a cool grandpa, and so Club Cs are some of my favorite shoes in the world. And then just growing up skateboarding and playing basketball. Skateboarding is what really got me into appreciating sneakers. Like when Chad Muska and Eric Koston skateboarded for eS, and I remember thinking, “I have to have those shoes. I have to skateboard in those.” I’m not precious about shoes. I like specific shoes that are expensive, but I’m going to beat the hell out of them. I don’t care about keeping them nice. That’s just me.

I know you mentioned that you didn’t go to school for art. Did you ever feel intimidated to enter this new industry and culture?

Absolutely. I think it’s only been maybe the last two years that I’ve totally let go of it. I didn’t go to art school; I don’t have an MFA. And there’s nothing wrong with art school or MFA programs. I don’t think, had I gone to art school, I would be making the work that I am making now because I would be overthinking it. I know how I am and how I was in school. I wanted good grades and tried hard, and it’s like, I’m learning now. I think going to school would’ve been really hard on me, but I can exist with it knowing that I’m going to make this art regardless.

What was it like working with UNDFTD, and do you want to work with more streetwear brands in the future?

I don’t really like the term “streetwear,” I think it has such weird negative stigmas. But I am open to working with brands that are innovative. The thing with UNDFTD was there was no product involved. It was my image on that billboard, and to me, that was a bucket list thing. Growing up in California and seeing that billboard, I had always thought, “I want to have work up there,” and it happened. I know some of the people that worked there, and it literally happened overnight, I sent them an image of the piece, and a week later it was on the billboard. I’m very careful about not putting my art on clothes, that can be a slippery slope. Not to say I never would, but right now, I don’t see that happening.

I get that. What would you say influences you?

Conversations with friends, spending a lot of time on the streets, spending a lot of time on the road. Those three things are probably my biggest influences. Also, seeing art, experiencing art, and stealing from myself [laughs].

How are you able to get your art out there, and have it be seen? What do you feel is your most efficient and productive platform for getting your work out there?

I don’t give a shit what anybody says about the sanctity of how art is supposed to be discovered. Instagram is the most important tool an artist can use. And I’d get in a fight defending that because I have the gallery that represents me in Europe that discovered me on Instagram. So many of the opportunities that I have had have come to me this way. By no means am I an Instagram artist, but I have used that channel to promote myself in ways that artists couldn’t have done 10 years ago. You can’t do it with just a website.

If you started creating before the rise of social media, would you be where you are today in your career?

Oh God, that’s a good question. I hope. I think that I’m pretty ambitious, and when I started making work seriously in 2012, there wasn’t so much sharing involved. I don’t know. We’ll never know.

How would you describe your audience? Who are the people that follow your art?

I would say it’s probably 25 to 40-year-old men. I was at an art fair a while back, and this woman said, “Oh, art for bachelors.” And I was kind of like, that’s not what I’m going for, but those are the people that were first receptive to my work, and now I’m growing my audience further.

Would you say your audience is closely tied to the basketball world?

It’s funny, I would think my art would be more tied to the basketball world, but I think a lot of these NBA players and people in that world aren’t that into it. It’s almost like, do you want always to experience that? There’s a lot of basketball franchises who have reached out about commissioning work and whatnot, and it’s just an interesting place to be in because the work’s about basketball, but at the same time, it’s not about basketball. If you have a basketball piece in every arena, it kind of loses its importance.

Photography by Derek Balarezo courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective

What’s the difference between art and consumer products?

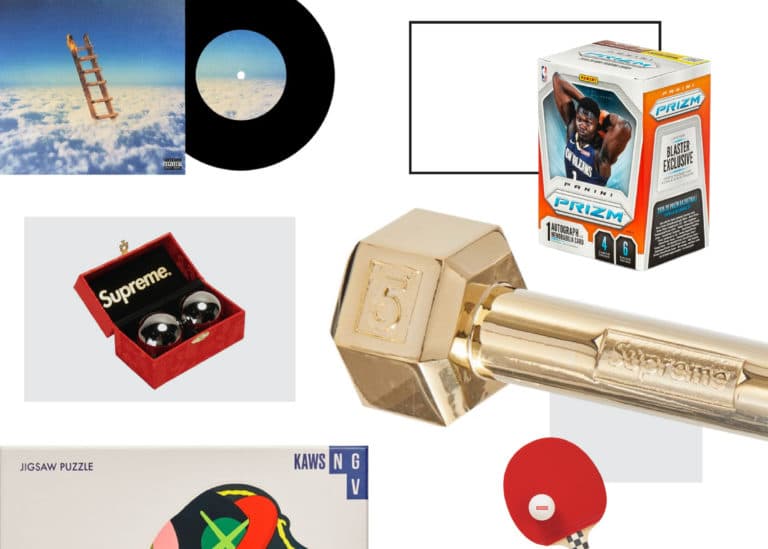

Well, it’s crazy right now because we’re seeing these worlds exist where people have edition type pieces that are, on a certain level, a consumer product, but it’s also art. I think it can be done tastefully and I think it’s a really great opportunity for someone who says, “Okay, I’m not just going to spend all my money on sneakers now or streetwear, I’m going to get this edition, or this print, or this small sculpture.” And I see more and more and more of that. And I think that’s cool because it’s breaking down that wall in the art world of intimidation where people think you can’t afford this and you can’t participate in that. And now, these are opportunities for people to participate, which is awesome.

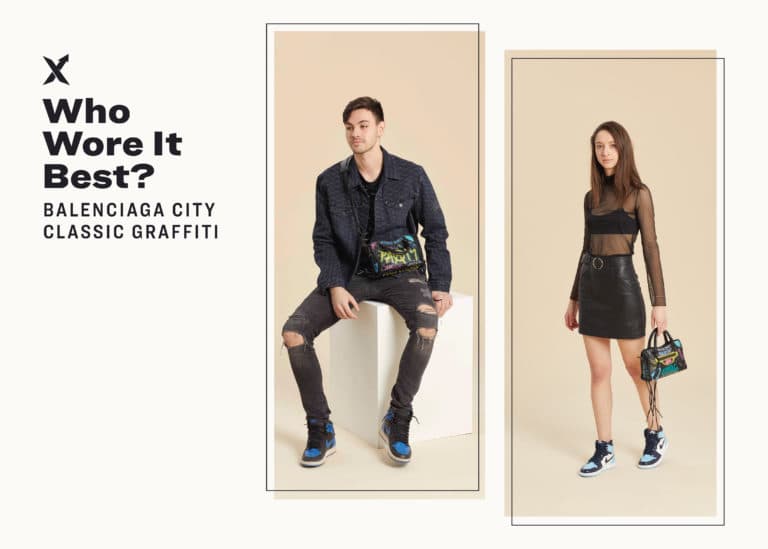

How do you feel about the cultural impact your work has on the sneaker, streetwear, and fashion communities?

It’s funny; it’s a gift and a curse. You put something out in the world, but once you put it out in the world, you don’t get to control who’s consuming it, what they’re saying about it. It is cool to be working with people and make friends with people that are big in fashion. Teddy [Santis] from Aimé Leon Dore, is like a mentor to me. I love him. He’s had my back since the jump, and there’s been a bunch of other people that through my art I’ve developed friendships with, from Virgil to Murakami. There’s this kind of professional relationship with them and respect that is awesome and very motivating to be around.

You mentioned that Teddy Santis has been your friend since the start. Do you think he’s motivated you to get to where you are?

It’s more just seeing what he’s developed for himself—he’s willed a lot of this and bet on himself, and I take that same energy and that bravado. He bought a piece from me and put it in the Aimé Leon Dore store. At first, I felt conflicted because I don’t want my work to live in retail spaces, but Teddy’s a friend, and it looks tasteful there. The crazy thing with the one piece that’s in the store is that an art buyer was visiting from Japan and asked if I would make a commission for one of his clients, and I said, “Sure,” and hashed out some details. From that commission that I made for that client, Murakami responded to that work and said, “Hey, I really like that strip you made, would you be open to making more? Would you want to have a show in Japan?” That literally came from having my work in Teddy’s store, that series of events. That’s where it’s art, fashion, and consumer goods are all just coexisting now. And I’m not going to fight it anymore.

The whole thing was kind of a chain reaction, and your career has reached that next level. Do you have any plans to try new forms or mediums?

Yeah, absolutely. I mean the show in Detroit, Encore, I’m showing this new body of work called “protection paintings.” It’s these steel panels that are painted with pearly auto body paint, and right next to them are tarps that are cut down from construction sites that are found on the side of the street. That’s a body of work that I’m really excited about. Some of it is influenced by sports. A lot of the colors I’m choosing are key American sports team colors. The scale of them is based on regulation-sized backboards. So it’s one of these things where they have nothing to do with sport, but there’s a vein of sport that exists within them.

Is there anything else people should know about you that you’d want whoever is reading this to know?

Hmm, I’m trying to think. I’m not originally from New York. It bothers some people that I use the Yankee cap motif, and they say, “You can’t do that. You’re not from here.” There are so many great artists who are not originally from New York that make New York-centric work or work that is a reflection of their love and respect for that city. I’m from Orange County, Southern California. I’m not hiding.

Finally, what does success look like for you, and how will you know when you’ve made it?

I will never make it, and I don’t ever want to make it. I always want there to be something else that I can try perfecting. But success to me is endurance and thinking about it in “we can.” We all eat well when there is a feast, but can you survive a famine? That’s my mentality. Right now, things are on a really good trajectory for my career. There’s going to be bodies of work that aren’t received as well as some of the other work I’m making now, so I need to be able to navigate that and grow from it. To me, being able to do that and trust myself consistently, that’s success.

Installation view of Encore, photography by Tim Johnson courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective

See more from Tyrrell Winston and learn about artists within the culture in “No Curator.”