In the world of high end watches, it can be difficult to reasonably discern the difference between say, a $10,000 watch and a $50,000+ watch that otherwise offer the same level of complication. How value is built and communicated in the world of 5, 6 and even 7 figure watches can be murky and outright nonsensical to outward observers. However, like many of the things in life, it comes down to the details, and the finishing of those details. The prime factors in the valuation of high end watches (excluding things like rarity, provenance, and brand prestige) comes down to two things, complication and movement finishing.

In a world where manufacturing has shifted largely to automation, finding signs of a human touch in the products you buy is rare, and often commands a premium. This is a reasonable expectation as things finished by hand are often skills not (yet) mastered by machines, and trades that still prize a human hand over a machine yield fewer goods. Think of the AMG engines assembled by hand in Affalterbach, or a wood table crafted by George Nakashima Woodworkers as compared to a Honda Civic, or an IKEA table. Each serve the same purpose, but the former will outperform or outlast the latter in a significant manner that affects the price tag in potentially dramatic ways. A high end watch boasts the same qualities you’d expect from hand made goods, and the craft is usually on full display through an exhibition caseback.

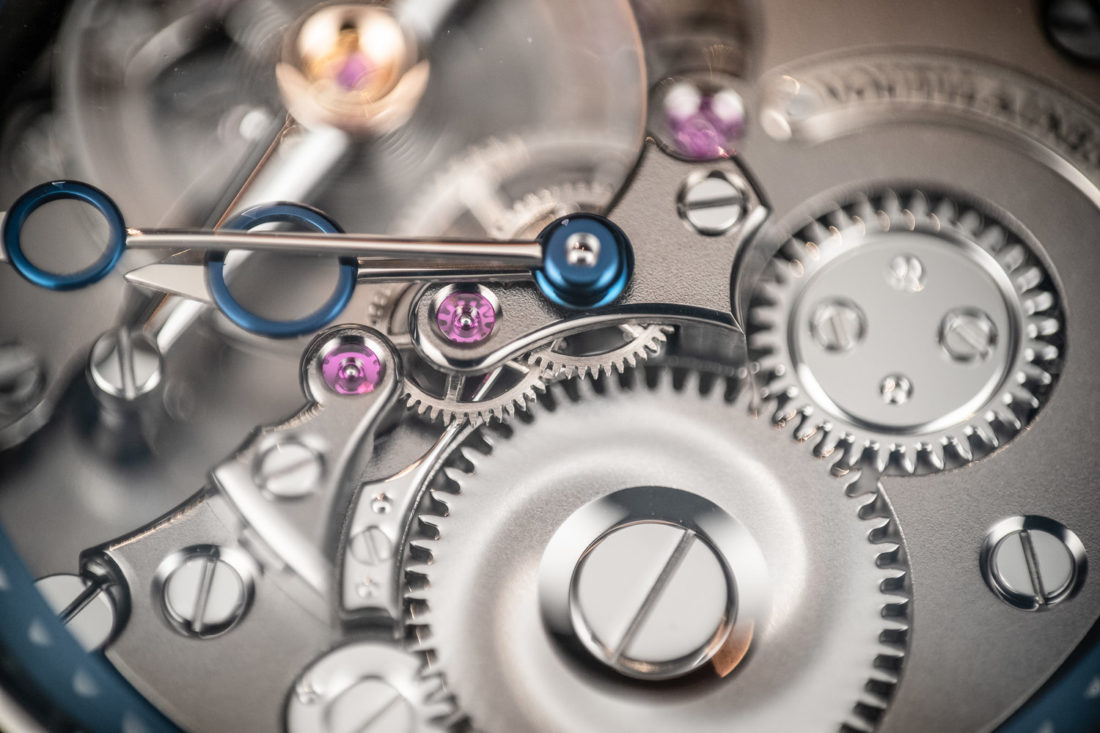

There’s a lot to look at when you flip a watch over. Bridges, screws, jewels, gears, springs and more all come together harmoniously to create a living mechanism. When decorated and finished properly, the whole becomes far greater than the sum of its parts. Not only does this benefit the aesthetic, but it protects many of the parts from corrosion over the long haul. The methods employed to achieve a well finished movement can vary by manufacturer or watchmaker, but there’s a few common threads you’ll end up recognizing across the spectrum of brands even price points. Below we break down some of the basics.

Geneva Stripes

Geneva Striping on the rotor, and bridge plates.

This is one of the most commonly used finishing methods for plates and bridges. The effect of waves in orderly rows is created by an abrasive tip running from end to end across the surface of the part. When viewed under differing light and angle, it creates an organic looking wave pattern. This is a finish found on watch movements across all price ranges, as it can be applied via machine, but the quality can vary by a wide margin. Many collectors will place a premium on well executed Geneva Striping, and while there is subjectivity involved, a keen eye will be looking for consistency in the application and depth of the striping, as well as minimal spillage into the anglage (more on that later).

Pearlage

Pearlage under the escapement and gear train, under brushed plates.

Another common base application is pearlage, which is a series of overlapping circles applied to large sections of plates, or recessed areas, such as the base of the cavity holding the escapement.

Anglage

Bridges and complication components featuring anglage.

Things really start to get interesting at the edges of the plates and bridges, where watchmakers apply a chamfer, or anglage to embellish shapes and define negative space. A well finished edge can elevate a movement as a whole, and the gap between average chamfering, and master level anglage is substantial. At a high level, the style in which anglage is applied becomes a hallmark of its maker, a signature that becomes instantly recognizable over time.

Polished & Brushed Surfaces

High polished anglage and bridge arms. Pearlage underneath. Photo credit Atom Moore.

Polished surfaces are finished to be fully reflective, and are found on cases and bracelets, as well as selectively within the movement itself. Anglage in particular is generally finished to a high polish to catch as much light as possible, accentuating the line. Levers and bars between bridges are often polished along their surfaces as they don’t have enough surface area to hold other finishes. Conversely, a brushed surface has a straight grain applied to it, absorbing light that hits it.

Materials & Components

The materials used to create the plates and bridges of a movement can have an impact on the overall aesthetic of the finished movement. A. Lange & Sohne use German silver – an alloy of copper, nickel and zinc – which has a soft, warm appearance when compared to steel. Likewise the smallest of parts can have a big impact on the visual identity of a movement, such as blued screws and jewels set into gold chatons, dotting the landscape of 3 quarter plates.

The manner in which all of the above are applied are unique to each manufacturer, and are often used to differentiate an in-house caliber from an off the shelf ebauche. The latter will be visibly rougher around the edges, with obvious signs of machining. The differences may be small, but when armed with an understanding of the methods and a loupe, these are the contrasts that jump out to a trained eye.

Just how much value any of this adds to a particular watch is subjective, but buyers are clearly willing to put their money behind the standard bearers of well finished movements from the likes of F. P. Journe, Patek Philippe, Kari Voutilainen, A. Lange & Sohne, and Philippe Dufour, to name but a few of the standard bearers of well finished movements.

Detailed view of the Kari Voutilainen 28ti, courtesy of watch photographer Atom Moore.

None of the above have an effect on the timekeeping of a watch, rendering them wholly unnecessary from a technical perspective. However, the emotional value they impart lend to the preservation of the craft as a whole, and deserve celebration as such.