During Spring/Summer 2004, Supreme released a series of long sleeve t-shirts featuring iconic Martha Cooper photographs. Martha Cooper established her reputation documenting early hip-hop culture and graffiti in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with many of her pictures included in her iconic 1984 book “Subway Art” published with Henry Chalfant.

So it makes sense that Supreme wanted to collaborate with Martha Cooper. The only thing that doesn’t make sense is why Supreme waited so long! When it comes to graffiti and street art, Martha Cooper remains the preeminent chronicler of the culture.

Below is our exclusive interview with Martha Cooper, were we talk about her life, her work, and her collaboration with Supreme. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

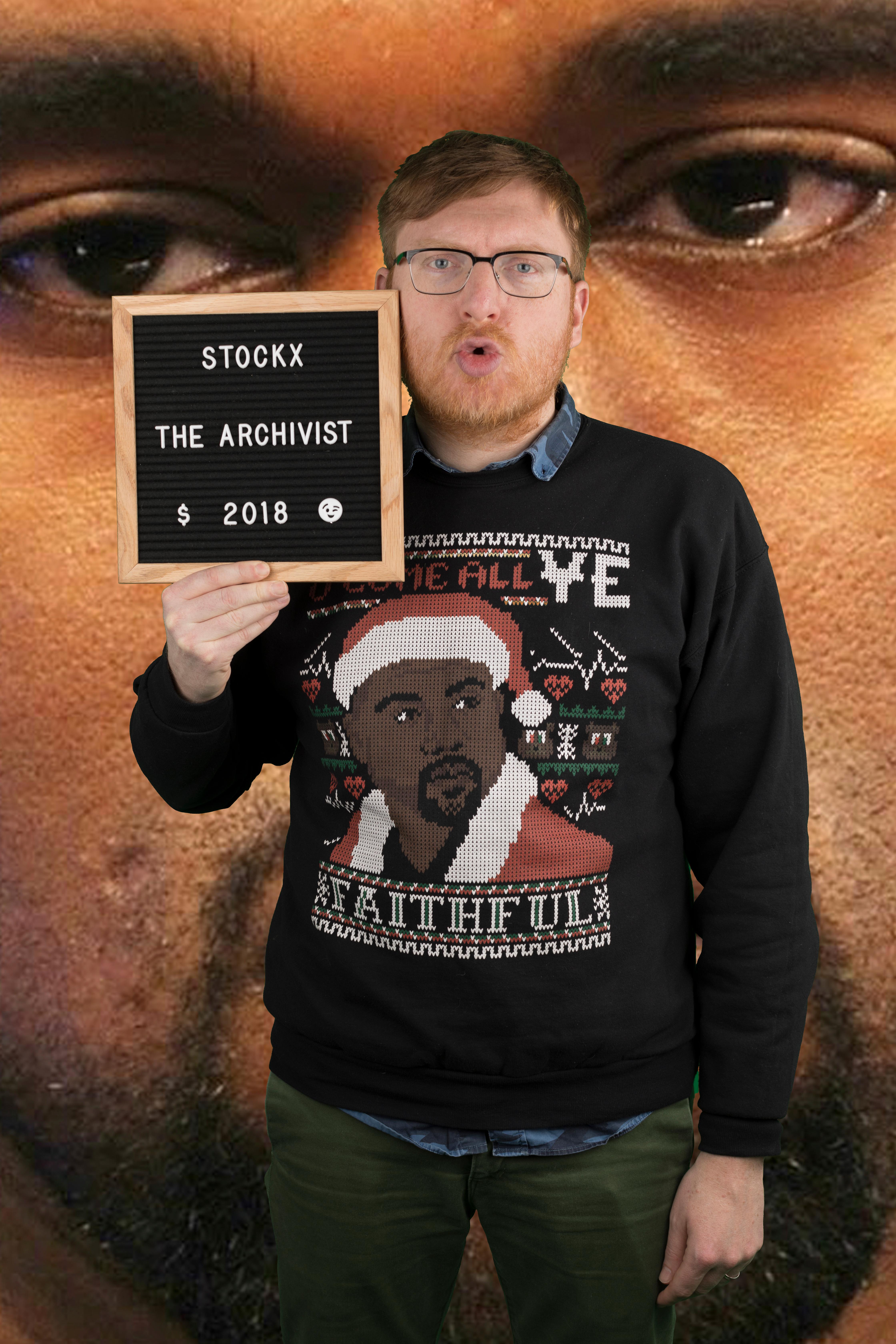

After you read this interview, you can check out all things Supreme here, as StockX takes a year-long look at the iconic streetwear company in honor of its 25th anniversary.

StockX: OK, let’s talk a little about your collaboration with Supreme. Were you aware of Supreme prior to working with them?

Martha Cooper: I was. There was the store [Lafayette St. in SoHo]. I used to walk by the store. Futura used to wear a Supreme cap. I knew that Supreme was an emerging thing. I think I walked in there once… I did know that shop and I vaguely remember the skateboard wall.

How did your relationship with Supreme come about?

How did your relationship with Supreme come about?

Somebody just contacted me. Maybe they emailed me… Somebody came over, maybe there had been some personal connection. Anyway, they came over and looked through my work and choose the pictures they wanted to use.

Was there any trepidation about working with Supreme?

There’s always slight feeling that you’re selling out. On the one hand, we all want to make money and artists need to make money to live. On the other hand…I don’t know if I felt any trepidation. The 1990s and early 2000s were a time when I needed the money. So Supreme is going to pay “x” amount? Fine. I think I even got a percentage off of sales.

Had you worked with other brands before? Was this something that you had wanted to do?

I don’t like my photos on t-shirts now, I don’t do that. I had a gallery that just closed—the Steven Kasher Gallery—but if I’m going to sell my pictures, I’m going to sell prints. I’m more into looking at a photograph as a photograph and not as a t-shirt. I’m way less inclined to have my work on clothing and things. I think I did one last year, though.

Would you work with Supreme again?

It would depend on what they wanted to do. I did a series with OBEY with t-shirts and prints and Shepard [Fairey] kind of “Shepard-ized” my photos. He did a skate deck, cap, and bag. Again I made some money.

And that’s the thing, artists have to make money; I have to make money. When I travel to festivals and things, there’s no honorarium or anything, just airfare, and hotel. Who’s got the money? Companies.

Are there any artists you think Supreme should be working with or you would like to see them work with?

BLADE would be my choice, but he’s already worked with Supreme. BLADE gave me one of the hoodies. In fact, I “Instagrammed” it. BLADE sent me a canvas with elements from two of my favorite whole cars he painted in 1980 and I’m wearing his Supreme hoodie. So you can see how Supreme used his swinging letters for their hoodies.

If BLADE hadn’t already worked with Supreme, he would have been at the top of my list [for working with Supreme]. He’s definitely at the top of my list for writing on trains. He did his own characters as opposed to adapting them. And he did his own letters. The swinging letters are my absolute favorite, and Supreme put it on the hoodie. I was so happy that he got the deal.

You’ve been pretty busy over the last year or so, and posting some fantastic pictures from all over the world on your IG. Would you mind talking about everything you’ve been doing?

Martha Cooper: More of the same: taking pictures, traveling around the world. I just in Mexico and I’m going to be going back to Mexico. I’m getting ready to go to India. I’ll be going to Haiti. There’s also a documentary about me coming out this year, “MARTHA.”

How have your views on art, photography, and the act of creation changed over the years?

For me, it hasn’t. I’m still taking the same pictures I’ve always taken. In terms of technology, it’s a complete change. Everything is now digital. It wasn’t easy for me to switch, but now that I did, digital is easier in every way—except with having to upgrade all the time. People think it’s free to take a picture, but the hardware is so expensive. If you compare the cost per photo between film an digital, I don’t know which would be cheaper. But I use digital. For my age, I’m pretty good.

You worked as a photographer for the New York Post during the 1970s. How did working for the newspaper affect your photography?

Shooting for the newspaper was an excellent experience. You’re out there every day with a huge variety of assignments. You don’t get to choose your assignments; you have to make it work somehow. Maybe the people didn’t want their picture taken; maybe you missed the event; maybe there were fifty other photographers there and you had to push through everyone to get the shot. There were a lot of challenges with working for the newspaper. On the other hand, while I was working for the newspaper, I was able to do this personal project. I would drive through Alphabet City and take pictures of kids making their own toys and that’s how I got into graffiti. The ones that I took—the shots became my book “Street Play.” I had film left on my rolls, so I would take pictures that I wanted to take and have them developed. If I didn’t take the pictures the remaining film would just be ruined anyway.

The photos I took then are the kind I still like to do. I still like going out on the streets and just shooting what I see. For me, that sense of discovery is important. You never know what you’re going to see, especially in New York. I prefer action shots to portraits or someone just sitting there. I don’t like to direct.

You’re one of the most important documentary photographers of the last fifty years. How do you think documentary photography has changed since the 1970s?

The internet has changed everything. You can watch the news in real time, while you’re working on something else. How can still photographers even work today? Still photography has been devalued a bit; Freelancers have a rough time.

Really, the whole internet has changed everything! There are certainly a million more photographers than there were when I was coming up. And that’s because of digital. Part of what is so wonderful about digital is that it balances the light. I think it’s hard for photographers to make a living today because there’s so much competition. There are so many more photographers today, and there are some extremely good ones out there, too. However, the photographers who came up with digital are probably not as technically proficient as I had to be back in the day.

You can now get really good pictures in low light—that’s one thing that’s changed about documentary photography. You can shoot in the dark now, and I’ve taken advantage of the technology. I have a book out with the 1UP crew from Berlin, “One Week with 1UP,” that I was able to shoot at night.

How have your views on graffiti and public art changed over the years, if they have?

I still shoot a lot of street art and artists who still do legal and illegal art—OSGEMOS, twins from Brazil, still do trains illegally and are represented by Lehman Maupin Gallery in New York. I enjoy both; the illegal stuff is way more exciting! The guys out there who are appropriating trains and walls for themselves: just writing your name on the wall. That keeps me going, the outlaw stuff.

The permission walls are something different. That’s why I’m going to ST+ART Festival in Delhi, India. I really appreciate being invited to come and participate. Who would have thought that graffiti would develop such a mainstream acceptance? I’ve been to Tahiti four times for this festival, the ONO’U Festival. The festival is advertised by the department of tourism!

When I think of your work, I immediately flash on an urban culture that’s hidden in plain sight—with New York the center of so much of your oeuvre. How has urban culture changed over the years you’ve been documenting it?

The internet, it’s changed the way everyone sees themselves, and culture. One little style thing can go viral in a minute, an hour, a day. The internet has definitely helped disseminate different styles of graffiti.

Because of the internet, there’s this global community of artists traveling around the world, festivals are inviting artists from all over the world and it happens in a way it never happened before. In the late 1970s, the idea of a writer going to Paris was so farfetched—but it did happen—and now these kids are traveling everywhere.

When I was documenting it [graffiti] in New York, I thought it would disappear and I would only have the pics. Who would imagine that companies would eventually start manufacturing spray paint for graffiti and street artists? Paint companies all over the world are now making hundreds of colors and all for graffiti. The tools have changed, too. Spray [paint] caps are manufactured now. Before you had to make your own spray caps or switch caps from different cans and things.