An inquiry into the nature and cause of Nike’s wealth at the dawn of sneakerhead nation imperialism . . . or . . .

. . . Can Nike get that resell cash?

PREFACE

We’ve been thinking about this topic for a while.

On one hand, there’s an easy answer which some will claim does not require the depth of our work. We recognize that some of the following may seem like overkill, and apologize for its overly-academic tone. On the other hand, there are still parts of this analysis left unexplored. The deeper we got, the more questions we found, and at some point we just had to put our pencils down.

Much of Campless’ work over the past year has touched on various aspects of this question and it felt like the right time to put it all together. The following is our current, best thinking on the subject, combining much of our old analyses with a lot of new. It is by no means complete, nor do we claim it is without error. But it’s what we’ve got.

If nothing else, we hope this adds some statistical evidence and detailed logic to the conversation. That’s always been our goal: not to end discussions, but to start them.

Enjoy.

INTRO

Collectively, sneakerheads made over $240 million gross profit selling sneakers on the secondary market last year. Many people believe this is money the sneaker brands, most notably Nike, could be adding to their bottom line. With the recent announcement that John Donahoe, CEO of eBay, has joined Nike’s board, it’s finally time for us to tackle the most complicated question in the sneakerhead game: Is Nike leaving resell money on the table?

Hypothesis: The existence of the resell market is evidence that Nike is not maximizing its profit

- The quick ‘n easy answer is that Nike can simply sell more or raise prices and capture its cut of the $240 million.

- The equally quick, equally easy, but opposite answer is that Nike chooses not to capture resell profit to ensure other sales.

Which is right?

Conclusion: Closer to B. It’s not that Nike chooses to forgo resell profits; rather, it can’t capture that money, even if it wanted to. Nike intentionally creates conditions – limited supply, heightened demand – that support the resell market, knowing millions of dollars will end up in the pockets of its most loyal customers (sneakerheads). Those same conditions also maximize retail sales, and to go after resell profits would risk disrupting the conditions which maximize retail profits.

In short, Nike cannot “get that resell cash” because:

- If Nike increases supply, it will lose sneakerhead sales.

- If Nike increases price, it will lose non-sneakerhead sales.

The retail market for re-sellable sneakers does not adhere to a true monopoly-based pricing model. However, examining concepts like supply vs. demand and price vs. quantity will help us better understand the fascinating business landscape Nike has built for itself.

SIZE OF THE MARKET ($800M+)

In 2013 there were approximately 2.1 million pairs of sneakers sold on eBay, totaling $275 million dollars (as previously reported). Approximately $75 million were non-collectible pairs, including children’s and women’s sizes, changing hands like any other commodity that has found its way to the grey market. The other $200 million is the eBay sneakerhead market – selling sneakers for more than retail price.

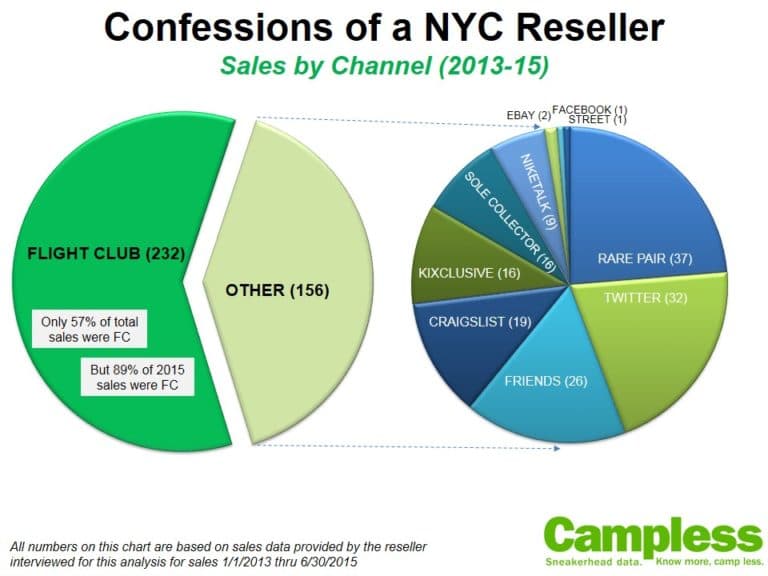

While eBay is by far the largest secondary market channel for collectible sneakers, the long tail of the market is extraordinarily long. Millions of pairs are resold via Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Craig’s List, Amazon, sneaker-only eBay clones such as SoleHub, sneaker blogs such as Sole Collector, sneaker forums such as NikeTalk, individual sneaker reseller sites such as OS Life, consignment shops such as Flight Club, sneaker shows such as DunkXchange and just good ole’ fashion face to face. The extreme fragmentation of the market makes it virtually impossible to quantify, but our current best estimate is that eBay is one quarter of the market, pegging total gross sales at approximately $800 million last year.[1]

THE OPPORTUNITY ($241M+)

The profit on that $800 million is represented by resell sales dollars in excess of retail price. For example, a general release (non-limited) pair of Air Jordans sells for $170 at retail. That same pair averages $265 on the secondary market, netting the reseller a quick $95. Here’s how that potential profit aggregates for Nike:

- 71% of the secondary market is deadstock (new) and 29% is used

- The average resell profit margin is 40% on deadstock and 5.5% on used

- Gross sales of $800 million therefore net $241 million in profit

- Nike (including Jordan Brand) accounts for almost 96% of the eBay sneakerhead market (in dollars)

- That’s $230 million (of $241 million) that might otherwise belong in Beaverton

Nike may be a $66 billion company[2], but you don’t get to be a $66 billion company by leaving $230 million on the table. Even Bill Gates bends down to pick up a fifty. There must be a reason why Nike lets thousands of teenagers pocket $95 crumbs or, alternatively, a scenario in which Nike will decide the $230M cake needs to remain whole . . . and be adorned with a swoosh.

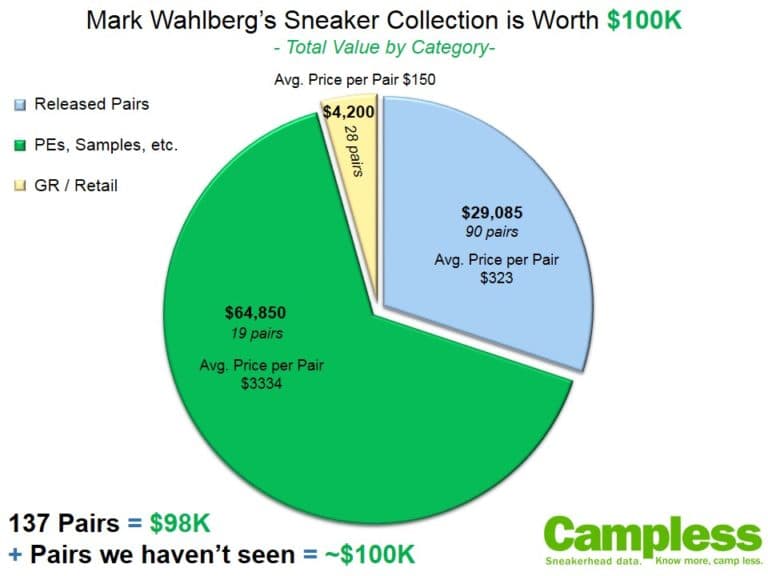

For purposes of this analysis we’ll focus on Retro Air Jordans, which have more consistent prices (retail and resale) than the wide variety of collectible Nikes. This will make it easier to analyze and highlight the issues inherent in the market. Plus, with almost one out of every three eBay sneaker dollars spent on Jordans, they’re a pretty good proxy for the sneakerhead market as a whole.

In 2013, Air Jordan Retro models 3-14 accounted for $63 million in eBay sales. When considering all Retros across all channels, the resell market for Jordans was approximately $266 million,[3] which breaks down to $191 million cost (retail price) and $75 million profit.[4]

Jordan Brand[5] had retail sales of $2.25 billion in 2013, approximately half of which were Retro, according to Matt Powell at Sports One Source, the leading retail sneaker data analyst.[6] Of the $1.125 billion Retro sales, $191 million worth of Jordans ended up on the secondary market. This (relatively) small segment, and the profit potential there versus Jordan Brand’s current retail profit[7], is our focus:

On the surface, Nike has the opportunity to pocket an additional $75 million – and that’s a conservative estimate. We assumed that additional profit potential exists only with the 4% of the population already paying resell prices, and not the 96% purchasing Retros at retail. Theoretically, if all customers were to pay a higher retail price, the profit potential could be as great as $443 million – not $75 million.

Even assuming the potential is only $75 million, when set against the $641 million retail profit Nike is currently making on Retros, that’s an extra 12%! Ask any global company how hard it is to add an extra 12 percent to the bottom line and I think we can all agree this is more significant than Bill Gates grabbing a fifty – particularly since Bill’s net worth ($77 billion) is greater than Nike’s.

To take it one step further, let’s remember that we’ve been working with 2013 numbers – and the sneakerhead market is growing fast. In fact, the resell market is projected to grow 50% over the next twelve months while the retail market has been growing at 5%[8]. This means the profit potential is actually closer to $112 million (not $75M), with a potential margin increase of 17% (not 12%).

MARKET DYNAMICS

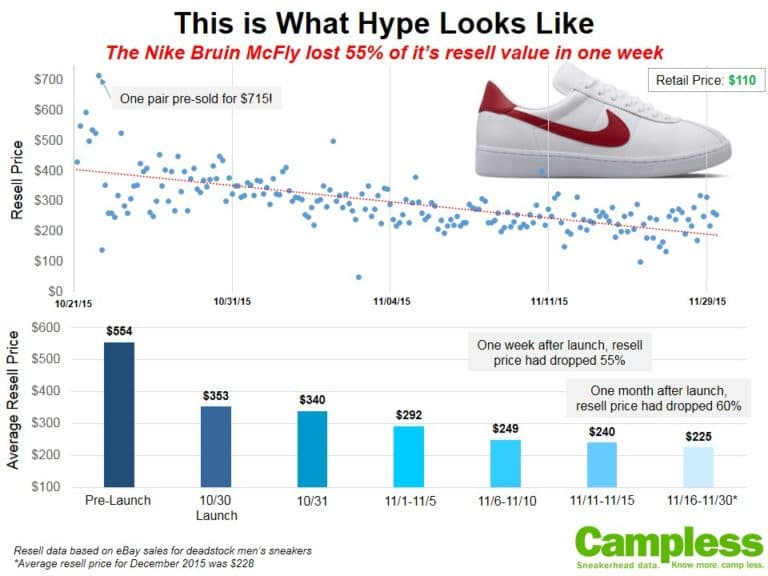

To properly examine these issues, we harken back to our Econ 101 days of supply and demand, and monopoly-based pricing. In a perfectly competitive market, price and volume are inversely related and meet at an optimal-profit point. But the sneakerhead market is not perfectly competitive. On the surface it may look like a stock market – perhaps the best approximation we have to a perfectly competitive market – but it actually has more similar characteristics to the illegal drug trade. The most important similarity is access to supply, where a central agent – in this case, Nike – meticulously (and secretly) decides how much product to release to the market, and when. Sneakerheads joke that it doesn’t matter what the shoe is – as long as it’s limited and Nike, they will buy it.

Today, more than 25 years into their sneakerhead training, Nike is clearly the intentional creator of sneaker arbitrage opportunities. Whether Beaverton executives admit to the intention or embrace a policy of willul blindness[9] is irrelevant. No one can reasonably argue that Nike doesn’t know exactly how its limited-edition releases create massive resell valuations; and no one can deny that Nike’s supply and demand decisions ensure a line of bleary-eyed campers outside every sneaker store in the country, every Saturday morning at 7:58am. The length of that line, and the length of time they’ve been living on the curb, is directly linked with the anticipated resale value of the sneaker being released that day.

This behavior is at the core of the question we are trying to answer.

ANALYSIS

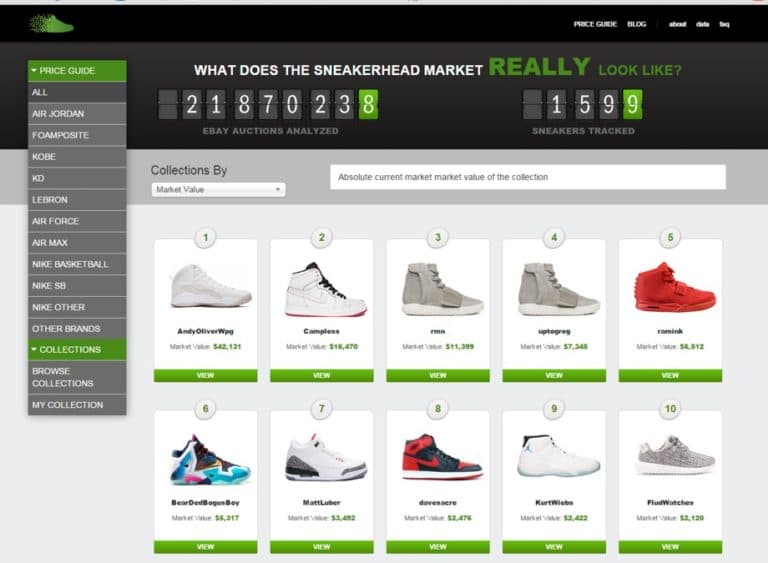

Campless is a “sneakerhead data” company. We’ve been tracking the resell market and analyzing eBay sneaker auctions for over two years. With the wealth of resale data available to us, we set out to learn what we could about demand elasticity and willingness-to-pay behavior in the secondary market in relation to retail sales and, hopefully, determine if Nike can make more money.

Air Jordans used to sit on shelves. As few as five years ago you could stroll into any random Finish Line a few days after release and have a good shot at finding a pair. As a result, there was no need for the size and speed of resell market that exists today, particularly around new releases. But Nike has become much, much better at predicting (or creating) sneaker demand and can now pinpoint production to ensure fewer pairs available than sneakerheads want to buy. In doing so, Nike sets in motion the conditions that create the secondary market.

The existence of a prolific secondary market results in a shoe’s actual value being greater than retail price and, thus, guarantees a complete sell-out at retail. Who wouldn’t buy item X for $170 if you knew it was worth $265? What if you have exactly 10 seconds to buy it, but if you later decide you don’t want it, there is a very liquid market for that item where you can easily net $265? Then would you buy it? Now you see why there is a guaranteed sell-out.

There appears to be three key principles to Nike’s resell strategy:

- Hold price constant: The price of Jordans has remained relatively constant in relation to inflation over the past 15 years. This allows consumers to plan expected expenditures. The average sneakerhead is only 21 years old and is actually quite price conscious. He spends a disproportionate percentage of his income on sneakers[11]. Certain shoes do command higher retail prices, but the difference in price must be related to an increase in quality or use of premium materials.

- Know demand: This is obviously the hard part. Nike and Jordan Brand have learned a lot about the price elasticity of demand curve for every Retro Jordan, down to the model and colorway. After 29 years of re-releasing the exact same 14 silhouettes, re-using the exact same colorways and re-serving the exact same customers, Nike has certainly passed its Gladwellian 10,000 hours of practice. Nike has had so much demand forecasting practice, in fact, many believe they are no longer forecasting it, but are in complete control of creating it. After all, Nike does spend $8 million per day on “demand creation”.[12] Regardless, there is a demand curve beyond which even Nike cannot force, and it must be acutely aware of that upper limit.

- Vary supply: The corollary “hard part” to knowing demand is the fact that supply variation is neither subtle nor nominal. In 2013, for example, the Air Jordan V Oreo sold 505,000 pairs at retail; the Air Jordan X Steel sold only 151,000 pairs.[13] They were both priced at $170 retail and are now both selling for about $225 on the secondary market. A resell premium like that can only exist if Nike is producing just less than actual demand. In other words, Nike needs to be pretty great at demand forecasting to be able to narrow a 234% retail volume difference down to the 4% of pairs that consistently end up on the secondary market.

This is what they do today. The question, then, is what can they change in order to make more money. Fundamentally, there are two options:

I – Increase supply[10]: Sell more pairs at the same price

II – Increase price: Sell the same number of pairs at a higher price

We know you’re not used to reading posts this long from us, so…

Welcome back.

Part I: Can Nike make more money by increasing supply? No.

As the Jordan V Oreo / Jordan X Steel example highlights, there’s not much room for supply error. What happens if Nike doesn’t hit its mark? To test this, we will hold price constant at $170 and assume that Nike knows the demand for sneaker X at $170 is 100 pairs. Let’s vary supply and see what happens under three scenarios:

SUPPLY SCENARIO ONE: Supply < Demand (Nike’s preferred strategy)

Demand is 100. Nike intentionally and specifically produces 96 pairs, resulting in a secondary market for 4% – the average percent of Jordans which end up on the secondary market.

Due to extremely passionate customers who are highly engaged on social media, combined with an over-crowded sneaker media market constantly starved for content, and the ever-present historical significance of Air Jordans, the relatively small supply/demand imbalance (4%) is amplified, causing the 96% to act with immediate purpose and take extraordinary measure to secure their pair at retail price immediately upon release. This includes camping out in front of a sneaker store or purchasing a sneaker “bot” for use online – neither of which guarantees a pair, by the way, but they at least increases the odds.

The actual value of the sneaker now rises from retail price ($170) to consumers’ expectation of resell price ($265), making the arbitrage opportunity a reality. The result: all 96 retail sell out instantly. On the corporate side, this ensures predictable (and high) internal sales targets, satisfying retailers and shareholders alike. Occasionally, Nike will produce even fewer sneakers (somewhere below 96) resulting in greater hype, higher resell prices and – just occasionally – some exuberant sneakerhead offering to trade his car for a pair. These drops (often called “quickstrikes”) are fewer and farther between and are used more to drive PR and brand cache than substantial sales revenue (see, e.g., the Yeezy 2 Red October).

SUPPLY SCENARIO TWO: Supply = Demand (Nike’s occasional strategy)

The primary negative repercussion of producing less than demand (besides lower sales) is the backlash from sneakerheads who lament “the game” and the hassle/money required to acquire a pair of Jordans. If Nike were to do this for every single release, the disgruntled voices would soon grow too loud. As it is, not a week goes by without at least a few people upset they couldn’t cop at retail – just get on Twitter any Saturday morning at 8:05am.

Nike mixes it up nicely, occasionally producing supply greater than 96, but attempting to stay below 100. This is often done for sneakers with large inherent demand such as the Air Jordan 11 silhouette, which has been the number one seller for each of the past three years (retail and resell). These are the pairs that drive retail sales. Because there is such high demand for these sneakers to begin with, reducing the secondary percentage to 1 or 2% will still ensure a complete sellout of these sneakers.

Occasionally, however, the precision of “knowing demand” and “varying supply” is not as accurate as Nike would like, and supply actually equals demand. In this case – if 100 are produced – sneakerheads will quickly figure out there is no supply/demand imbalance; they will know they can walk into any store and cop a pair. The perceived value will equal the retail price and suddenly the sneakerheads’ true demographic buying patterns will emerge, likely adhering to traditional monopoly-based pricing with high demand elasticity. People will think twice about paying $170 for their thirty-fifth pair of sneakers[14], particularly a pair anyone can cop.

This is the exact scenario that has played out in years past as Nike was still refining its marketing expertise. In 2000, for example, this author bought a pair of Air Jordan 11 Concord at a retail store one full month after they released. When the same shoe was re-released in 2011 riots were reported nationwide.

The result is that, at a production of 100 pairs, Nike might not even be able to sell the 96 it could sell at a production of 96. This may be what has happened with LeBron James’ signature line the past few years. The LeBron 11, for example, has a retail price of $200 for general release, non-limited pairs. Anyone can walk into Finish Line and purchase one. Because they are not limited and have a very high retail price point, over half of LeBron’s line trades on the secondary market at a discount and often sits on retail shelves until clearance. From Nike’s perspective this may be OK, as there were over 50 different colors of the Lebron 11 and this might be the way to maximize retail sales of the entire model, but its definitely not how to maximize sales for a single sneakerhead pair.

SUPPLY SCENARIO THREE: Supply > Demand (Nike avoids)

As supply starts to exceed demand, the erosion of the secondary market (and thus retail sales) happens even quicker. Putting the three scenarios together, the sneakerhead supply/demand curve might look like something this:

This chart shows, as discreet scenarios, the instantly circular market dynamics which take place. There is “sneakerhead demand” for a particular sneaker given the expected value of that sneaker on the secondary market, which can be fairly well predicted by Nike when keeping price constant.

If the availability of that sneaker is sufficient to supply all of the “sneakerhead demand”, there is no longer a need for the secondary market, which causes the price of the sneaker on the secondary market to drop below expected resell price, which causes the actual demand to fall below “sneakerhead demand” and the actual sales to be even lower than when production was more limited. The decline will eventually level off to what is essentially “non-sneakerhead demand” – i.e., the secondary market evaporates and Nike struggles to maintain its current retail profits. The exact scale and scope of the drop to “non-sneakerhead demand” is unknown (at least by Campless) but its existence is definitely real.

Alternative Supply Strategies: It’s worth noting that Nike has several alternatives by which it might increase sales without crossing the supply = demand threshhold. These options include: restocks, re-releases and Retro-ing new models. To give you an idea of how seriously Nike is pursuing these strategies, consider that in 2009 they Retro-ed 13 different Air Jordans. In 2013 that number was 39 and, as of June this year, was on pace for 44 in 2014. The nuance and expanse of these strategies, however, requires a separate analyses for each. In the interest of brevity (of which this paper is sorely lacking) we’ll save that work for another day, but fully expect each to have a “decline to non-sneakerhead demand” component.

Returning our attention to the supply/demand analysis, we have expanded on the three scenarios by statistically testing the various relationships between retail volume and resell price premium (price paid above retail on the secondary market). If an increase in retail supply causes the resell price premium to drop (or disappear), it supports the notion that the resell market will collapse.

The answer: It does.

Analysis Methods

- Analysis Type: Simple linear regression

- Data Set (resell): 142,882 eBay sales for 65 Air Jordan Retro sneakers released in May 2012 or later, and sold through Feb 2014, all in deadstock (new) condition. Full sneaker list in Appendix.

- Data Set (retail): Top 20 Retro Jordans by retail sales. Provided by Matt Powell at Sports One Source.

- Calculated Variables: A) Resell Price Premium = (Average Resell Price / Retail Price) – 100%. Ranged from 8.5% to 375.3% (i.e., 8.5% above retail). B) eBay-to-Retail Volume Ratio = eBay Volume / 2013 Retail Volume. Ranged from 0.3% to 2.5%

Statistical Findings

- Finding #1: Higher eBay volumes are correlated with higher retail volumes[15], suggesting that if Nike releases more pairs at retail, more pairs will end up on the secondary market

- Finding #2: Higher eBay volumes are correlated with lower resell price premiums[16], suggesting that (when combined with Finding #1) if Nike releases more pairs at retail, that sneaker will have a lower resell premium – i.e., lower profit potential

- Finding #3: Higher eBay-to-Retail volume ratios are correlated with higher resell price premiums[17], suggesting that the greater the opportunity for profit, the greater percentage of retail releases that will end up on the secondary market

If we put it all together: Nike increases supply –> more pairs end up on eBay –> resell profits decrease –> the percentage of sneakers which end up on eBay decreases –> the secondary market contracts / collapses –> “sneakerhead demand” for retail sneakers decreases / disappears –> retail sales decline to “non-sneakerhead demand”.

In short, if Nike increases supply, it will lose sneakerhead sales.

————————-

Part II. Can Nike make money by raising prices? No.

If a pair of Jordans sells for $170 at retail and $265 on the secondary market, why can’t Nike simply raise its price to $265? Is the price elasticity of limited-release sneakers so small that Nike can raise prices on their entire Air Jordan Retro line and expect sales to decrease at a slower rate? Given the dynamic of the secondary market, the appropriate way to test this may be to ask:

Will sneakerheads continue to pay a premium for Air Jordans on the secondary market, regardless of increased retail price? If so, then the actual value of the sneaker will still be greater than retail, the sneakerhead demand concept will still hold true and the supply half of the equation (as detailed above) will also hold true.

We’ll attempt to create a framework and look at scenarios under which it would be profitable for Nike to raise prices and, perhaps, find the equilibrium of greatest profitability.

There are two general scenarios: a) The sneaker does not trade at a resell premium and is therefore only “worth” the new retail price ($265); or b) The sneaker continues to trade at a premium and is now “worth” more than retail (>$265).

PRICE SCENARIO ONE: Resell Price = Retail Price

The sneaker does not trade for a premium and is therefore only “worth” the new retail price ($265):

If the sneaker does not trade for a premium, we can use our supply example to show that when supply equals demand – or, in this case, when actual price equals actual value – Nike will actually sell less then when there is a supply imbalance. And that makes sense, right? The consumer is no longer getting a deal, so the marketplace question is no longer “Do you want a $95 value?” but, instead, “Do you personally value this particular shoe at $265 or greater, particularly in light of the fact that you probably own 34 other pairs of shoes and already spend too much money on shoes and don’t usually buy shoes that aren’t limited?” It’s a much different question (as well as a poorly written run-on sentence). But the conclusion is clear: if the resell premium disappears, this is not an option for Nike to make more money.

PRICE SCENARIO TWO: Resell Price > Retail Price

The sneaker continues to trade at a premium and is now “worth” more than the new retail price (> $265):

The first thing we did was try to prove that the resell premium will endure in the face of increased retail price. We ran several different regressions in search of any correlation between an increase in retail prices and the resell price premium (as a percentage) and did not find anything statistically significant. Unfortunately, the absence of evidence for a correlation is not proof that one does not exist – so we can’t say anything definitive here. We can’t say the resell premium will endure; but we can’t say that it will go away either. With that in mind, let’s assume that the sneaker does, indeed, continue to have a resell price premium and look at a few issues:

Non-Sneakerhead Demand

We know that 4% of Air Jordans sold at retail end up on the secondary market. This means that at least 4% of Retro Jordan customers are willing to pay $265 for a pair of sneakers which value is $265. These sneakerheads are paying fair market value. 96%, however, are willing to pay $170 for a shoe worth $265 – and we know that at least some of them are willing to do so only because it’s worth $265, or only because of the opportunity for a 56% return on their money (either now or in the future). The question, then, is how many of the 96% do we lose as the initial investment increases above $170 and the return on investment falls below 56%?

Returning to the supply example, we may actually know (or Nike may actually know) what percentage of the 96% are buying any particular pair of Air Jordans because they inherently want it, as opposed to wanting the value. The number should be the same number of people who will buy the sneaker when supply exceeds demand. In the supply example we said that “non-sneakerhead” demand was hypothetically equal to 88%.

[Keep in mind that 88% is purely made up. Our analysis doesn’t fully account for the fact that the percentage of people who “inherently want” a pair of sneakers is very tightly linked to the brand value of the shoe . . . and the brand value of the shoe is very tightly linked to the hype . . . and when supply is greater than demand, hype will diminish. This reinforces the point we are driving towards – i.e., that increasing price is not a good idea – but for the purposes of this analysis, let’s assume that Nike’s production is 96% and “non-sneakerhead” demand is 88%. Remember that none of the calculated numbers actually represent Nike’s business results.]

Retail Price / Profit Tradeoff

If 88% represents non-sneakerhead demand then, presumably, at least 8% (96% minus 88%)[18] will buy a $265 shoe so long as it is trading at a premium. This means that while Nike can make more profit from the 8%, the remaining 88% will behave like a traditional monopoly-based pricing population: price goes up, sales go down.

The simplistic analysis, then, involves two sliding scales:

- As retail price goes up from $170 to $265 . . .

- Retail sales go down from 96% to not less than 8%

In this scenario, the breakeven point is 42%[19]. If retail price goes all the way to $265, and retail sales drop all the way to 42%, Nike will still make the same amount of profit – in theory.

Additional Negative Implications of Raising Retail Prices

The problem with this theory is that for each shoe which becomes available at retail because it’s too expensive for a non-sneakerhead to buy, that’s one more pair that is available for sneakerheads. This makes the 96% production act closer to 100% availability – which means the resale price premium will slowly decay. At 42% retail sales there will be 58% supply available to feed the 4% sneakerhead demand. Under this scenario, the only way for Nike to ensure a resell price premium is to produce fewer shoes. But to do that breaks the core hypotheses we are trying to prove – i.e., that Nike can increase profit by selling the same number of shoes at a higher price.

In fact, if Nike decreases volume in reaction to increased retail prices, the resell profile will fundamentally change and or bump up into the next tier of product. For example, what starts as a high volume general release (AJ5 Laney $170) will become a limited general release (AJ5 Bel Air $185), then a premium limited release (AJ5 3Lab5 $225), an ultra-premium general release (AJXX8 $250) and finally an ultra-premium limited release (AJ Shine $400). The point is – it’s crowded up there. Nike better know exactly how to position its new, more expensive sneaker. If the Laney V had been $265 instead of $170, what would have happened to the Bel Air, 3Lab5 and XX8?

While we have intentionally stepped over some rabbit-holes of analysis here, in the end, these factors all point in the same direction: raising price is not a great option. At best there may be an opportunity to increase retail price just a few dollars without significantly disrupting the rest of the ecosystem. But, all things being equal, they can’t raise prices at a rate greater than inflation without losing non-sneakerhead sales.

In short, if Nike increases price, it will lose non-sneakerhead sales.

Alternative Price Strategies: “All things being equal” is one maxim Nike has no intention of adhering to, as evidenced by its pursuit of alternative supply strategies (restocks, re-releases and more Retros). In fact, this might be exactly what we’re seeing with rumors of “re-mastered” Jordan Retros that will retail at $190 next year. An increase to $190 the year after the $160-to-$170 jump would no longer be moving lock-step with inflation (assuming no hyper-inflation in 2015), so the key question is whether the $190s are replacing the $170s, or merely augmenting them. Basically, is Nike creating a new Retro tier, or is it pushing up floor? If its pushing up the floor, the question will be whether the “re-mastered” product is a sufficient increase in quality (either real or perceived) to warrant a greater-than-inflation price hike. Regardless of the answer, we’re seeing the emergence of new pricing strategies, which should be fun to watch play out.

CONCLUSION

Certainly no one needs Campless to tell them that Nike knows what it’s doing. But a central takeaway from our work is definitely . . . Nike knows what it’s doing.

The numbers say it’s pretty difficult for Nike to cut into sneakerhead profit without cannibalizing retail sales/profit to a greater degree. Bottom line, if Nike increases supply or price too much, the secondary market will collapse, resulting in fewer pairs sold at retail.

- Supply: With only 4% of retail sales flowing to the secondary market, the supply/demand balance is too delicate for Nike to try to increase sales volume beyond what it knows to be “sneakerhead demand”.

- In short, if Nike increases supply, it will lose sneakerhead sales

- Price: If Nike increases price faster than inflation, some percentage of the 96% who purchased at retail will follow the textbook demand curve – price goes up, sales go down. In addition, the resell premium could disintegrate, and the current product/price tier structure will be disrupted.

- In short, if Nike increases price, it will lose non-sneakerhead sales

Nike chooses to operate where it’s at given the current retail and resell marketplace, which makes sense logically, considering that they have more or less created the conditions for both. For every inch they can push the retail demand curve upwards with marketing, they are prepared to capture greater retail sales. But Nike has too much to lose by going after resell profits. This is not necessarily the case for their competitors.

Not surprisingly, other brands – particularly start-ups that don’t have X billion dollar year-over-year growth targets – appear to be using lessons learned from Nike to create a new premium retail model. The new model builds in the resell premium to the retail price. One such sneaker brand, Buscemi, sells $800 retail sneakers and employs a demand creation strategy built on extreme exclusivity and intentional unavailability (and possibly paying rappers to rhyme their brand name with “sashimi”).

Nike may never be able to (or want to) cross the resell profit threshold, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t maximizing profits. In fact, its likely just the opposite. By allowing sneakerheads to compete for the resell profits, it ensures a predictable resell market – and with it predictable retail customers. This allows Nike to pursue new strategies to capture greater retail sales by further leveraging the same conditions that create the resell market in the first place.

We are already starting to see this on both the supply side (restocks, re-releases, more Retros) as well as the price side (re-mastered retros, more price tiers) but, frankly, these are the obvious and logical extensions of their current model. What we’ve come to expect from Nike in all facets of their business is innovation: innovation of product, innovation of marketing and – perhaps now with the eBay CEO joining their board – innovation of sneakerhead business model.

There’s a reason for the line outside of every sneaker store at 7:59am every Saturday morning.

There’s a reason every pair of Jordans is sold out, nationally, by 8:01 am.

There’s a reason sneakerheads made $240 million profit last year.

There’s a reason the resell market is projected to grow 50% in the next 12 months.

There’s a reason none of these things existed five years ago.

That reason is Nike.

We can only imagine what this list will look like five years from now, when the reason is “Nike and eBay working together”.

———————————————————–

APPENDIX

Sneakers analyzed in regressions:

| AJ1-Black-Blue-2013 | AJ5-Fire-Red-2013 | AJ9-Johnny-Kilroy |

| AJ1-Black-Gold-2013 | AJ5-Fire-Red-Black-Tongue-2013 | AJ9-Motorboat-Jones |

| AJ1-Bred-2013 | AJ5-Grape-2013 | AJ9-Olive-2012 |

| AJ3-Crimson-2013 | AJ5-Laney-2013 | AJ9-Photo-Blue |

| AJ3-Fear-Pack | AJ5-Oreo | AJ9-Slim-Jenkins |

| AJ3-Fire-Red-2013 | AJ5-Valentines-Day-Women | AJ10-Bobcats |

| AJ3-Joker-ASG-2013 | AJ6-Golden-Moments-Pack | AJ10-Cool-Grey-Infrared |

| AJ3-Powder-Blue | AJ6-Infrared-White-2014 | AJ10-Doernbecher |

| AJ3-White-Cement-88-2013 | AJ6-Olympic-2012-London | AJ10-GS-Fusion-Red |

| AJ4-Black-Cement-2012 | AJ7-GMP | AJ10-Powder-2014 |

| AJ4-Fear-Pack | AJ7-J2K-Filbert | AJ10-Steel-2013 |

| AJ4-Fire-Red-2012 | AJ7-J2K-Obsidian | AJ11-Gamma-Blue |

| AJ4-Green-Glow | AJ7-Olympic-2012 | AJ11-Low-Pink-Snakeskin-2013 |

| AJ4-Military-Blue-2012 | AJ7-Raptors-2012 | AJ11-Low-Reverse-Concord |

| AJ4-Thunder-2012 | AJ8-Bugs-Bunny-2013 | AJ11-Playoffs-Bred-2012 |

| AJ4-Toro-Bravo | AJ8-Phoenix-Suns | AJ12-Gamma-Blue |

| AJ5-3Lab5 | AJ8-Playoffs-2013 | AJ12-Obsidian-2012 |

| AJ5-3Lab5-Infrared | AJ9-Bentley-Ellis | AJ12-Taxi-2013 |

| AJ5-Bel-Air | AJ9-Calvin-Bailey | AJ13-Bred-2013 |

| AJ5-Black-Grape-2013 | AJ9-Cool-Grey-2012 | AJ13-He-Got-Game-2013 |

| AJ5-Doernbecher | AJ9-Doernbecher-Pollito | AJ13-Squadron-Blue |

| AJ5-Fear-Pack | AJ9-Fontay-Montana |

[1] Despite the difficulty in quantifying the size of the non-eBay market due to extreme fragmentation, our estimate that eBay is 25% of the market is based on a logical but conservative approach, broken into three parts: 1) We’ve quantified the number of sneaker listings on non-eBay channels with substantial volume, including Kixify, Sole Collector Marketplace, NikeTalk and several reseller websites. Assuming each of these resellers have lower turns than eBay, we’ve estimated sales using eBay’s listings-to-sales ratio; 2) We’ve interviewed people who are knowledgeable about the industry, including some who sell on both eBay and elsewhere; and 3) Most importantly, a handful of non-eBay resell businesses – some quite significant – have shared their sales data with us. Each reseller operates in a different non-eBay channel, including consignment, store front, sneaker show, independent website, Twitter and Instagram. Based on what we know about these particular resellers in relation to their market – i.e., our estimate of their market share of channel compared to the other major resellers within that channel – we’ve estimated the size of each channel. By combining and comparing what we’ve learned from each of these three methods, we currently estimate eBay to be no greater than 25% of the market, which puts the entire market at $800 million for 2013. In other work, Campless has projected the secondary market for sneakers to exceed $1 billion over the next 12 months. For purposes of this analysis we will use historical (2013) actual numbers for both retail and resell sales, whenever possible.

[3] In other research, Campless estimates that 1% of new release Air Jordan’s end up on eBay. This implies 4% in total because we’ve estimated eBay to be one quarter of the market. Jordan Brand had retail sales of $1.125 billion for Retro Jordans. This would be $45 million (at retail) on the secondary market. At an average markup of 60% on retail equals $72 million at resell, and significantly short of the $266 million reported above. The difference is a function of the fact that in any given year, approximately 75% of resell sales are for sneakers which had released in a previous year. Because we can assume this happens consistently year after year, and to keep the analysis simpler, we’ve assumed that all resell sales take place in the same year as their retail sale.

[4] $191 million was calculated by applying the resell profit margins and volume percentages for deadstock (new) and used. For Jordans, 70 percent of the secondary market is deadstock and 30 percent is used. The average profit margin is 38 percent on deadstock and 7 percent on used. Using these numbers we can take the $266 million resell sales, back out profit and are left with $191 million retail price.

[5] Because Jordan Brand is owned by Nike, we use Jordan Brand and Nike interchangeably throughout the rest of this analysis, sometimes referring to the actual sales, other times to the global business decisions.

[6] Matt Powell, Sports One Source

[7] Retail profit is calculated using profit margins and volume percentages for direct-to-consumer (DTC) and retail partner channel sales for Retro Jordans. Retro Jordans sell 15% DTC and 85% channel. They have 60% margin DTC and 40% margin channel. Matt Powell, Sports One Source

[8] Matt Powell, Sports One Source

[9] This is our anecdotal opinion based on the public statements we have seen or read from Nike in the past few years. We did not speak with anyone from Nike for this work.

[10] Technically, this should be “volume” and not “supply” since we are talking about a revenue calculation (p x q) rather than supply vs. demand. The point, however, is that Nike’s supply = volume, since the goal of their strategy is to leave no stagnant inventory in the retail market.

[11] 98% are male. 63% of sneakerheads make less than $25,000 a year (including those still in school), but 84% buy at least one pair of sneakers per month. Campless Sneakerhead Survey, June 2014

[13] Matt Powell, Sports One Source

14] The average sneakerhead has 34 pairs of sneakers. Campless Sneakerhead Survey, June 2014

[15] Regression results: Simple linear regression of Retail Volumes on LN (eBay Volumes). R-squared = 0.28. F(1,15) = 5.86 p = 0.029. Estimated beta = 79,989 (standard error = 33,039, t = 2.42, p = .029). Regression equation: Retail Volume = 79,989 * LN (eBay Volume) – 272,022

[16] Regression results: Simple linear regression of LN(Premiums) on LN (eBay Volumes). R-squared = 0.115 (very small, but we are not arguing that we can predict premiums; primarily interested in slope). F(1,64) = 8.33 p = 0.005. Estimated beta = -0.179 (standard error = 0.062, t = -2.886, p = .005). Regression equation: LN (Premium) = -0.179 * LN (eBay Volume) + 0.523

[17] Regression results: Simple linear regression of eBay-to-Retail Volume Ratios on Premiums. R-squared = 0.24. F(1,15) = 6.09 p = 0.026. Estimated beta = 15.34 (standard error = 6.21, t = 2.47, p = .026). Regression equation: Premium = 15.34 * eBay-to-Retail Vol. Ratio + 0.19. Slope of regression equation (the beta) implies that a shift of demand overflow from 0.3% to 2.5% is associated with nearly a 35%-pt increase in the price premium (e.g. from 25% premium to roughly 60% premium). Note that if the lowest volume ratio sneaker (AJ 11 Low Reverse Concord) had been dropped, the effect would have been even more powerful, but there is not a particularly good statistical reason to remove this, besides its high leverage on regression equation.

[18] It’s 8%, not 12% (100% minus 88%) because Nike will still need to produce less than demand in order to ensure the secondary market, so we continue to use 96%, as before.

[19] Average retail margin for Jordans is 43% (as explained in a previous footnote) which equals a profit of $73 per shoe. The new retail profit will be $168 ($73 + $95). The breakeven point = 96% * (73 / 168) = 42%.