“No Curator” focuses on the most important and cutting edge visual artists who create and draw inspiration from the interconnected cultures of StockX. In this installment of “No Curator,” Christophe Roberts talks about his Chicago upbringing, how he got started working with shoeboxes, and much more.

Be sure to check out Christophe Roberts’ Instagram for more.

The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

It’s great to have you be a part of our No Curator series. Would you please introduce yourself?

This is Christophe Roberts. I’m an artist here in Brooklyn, New York, and I’m originally from Chicago. My family is from the Bahamas and Alabama, so it’s a weird match up; I’m half Bahamian and then half Alabamian.

You’re definitely drawing on a range of cultural histories and experiences. What was it like growing up with? Do you have any especially vivid memories?

I’m a very visual person with memories and can pinpoint several moments of fascination with the creative process. There’s a lot of moments, so it’s hard for me to pinpoint just one, but a moment that particularly speaks out to me has to do with a babysitter I had growing up. His name was David, and he was a fly-boy. He was the roller skating rink referee. I think at that time, my mom was a single parent and was really trying to find a male figure for me to be around and to keep me cool. So when he would babysit me he would throw on anime all the time. At the time, I didn’t understand how intricate animation could be. Almost every other time he babysat me, he’d play this film Akira for me, and I would be pausing the VCR, drawing frames of that movie. I can also remember some of my time at the summer camps and art centers in Chicago just because my aunt ran a lot of the inner-city programs for the projects, like Cabrini-Green and the YMCA. So I was always around different kinds of kids. Hip-hop was also very essential to me, along with graffiti and being a b-boy.

It sounds like anime and hip-hop were important to you growing up and thinking about art. How else did your childhood influence your art?

I first started building sculptures at a very young age, with paper plates at my aunt’s house in Chicago. I would make toys and different arrangements out of things I would find around the house. For some reason, I had a strong liking for paper plates; I was a weird kid. I was into really gory stuff when I was young, like Hellraiser and aliens and sci-fi, so I think I always took a liking in creating things from scratch, or just figuring out ways to work with things in my environment, like the costumes and set designs from the stuff I was into. My aunt and uncle were also really heavy in the art scene and fashion scene, so that had a lot of inspiration on the work coming later down the line.

As you were taking all these influences in, when did you first start to think about making art or being an artist?

I thought about being an artist from the very beginning. Elementary school was when I first started pitching and selling artwork. I went to this public school in Chicago that’s in the dead center of the city. I was a big comic book nerd and would spend a lot of my time tracing and drawing a lot of different characters that I was into. I convinced all the kids in my class to hand over their lunch money to fund this project to create a comic book, which I eventually did. I don’t think any of the kids got any return on that investment, but I finished the comic book. I would later use that comic book to qualify for this special program in Chicago that was at this private school where they let like one bad kid in once a year. Kids from some very elite families in that area went to that school. But ever since I was young, I’ve been either drawing or tracing or creating things from scratch. When I first started, I was a master illustrator, and people started to notice that, which led to me stumbling upon the path of becoming an artist now.

Ok, we’ve covered how you developed your skills growing up, and your influences. Now, as a professional artist, how do you create? What is your process?

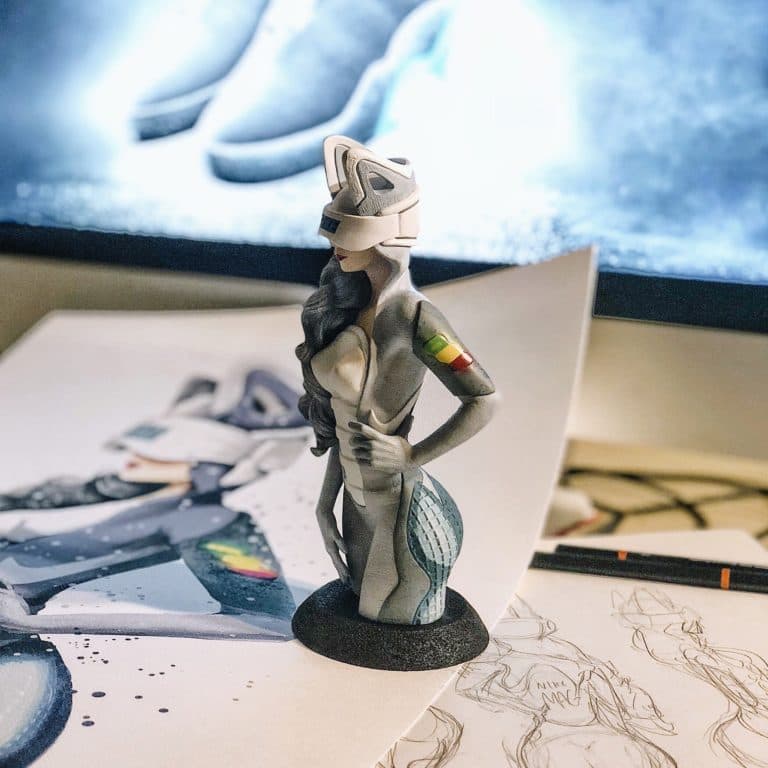

I like to sketch, and I run through a bunch of rough sketches, which is the first phase of coming up with an idea for a piece. Those rough sketches can be pretty rough, but they are all I need to know how I will execute. These sketches can be inspired by anything, like emotions. I also reference a lot of different images from all different genres: It can be an African mask, a Gundam character, or an excerpt from African folklore. I could be looking at architecture from one of my favorite architects, Ando, to other artists like El Anatsui, who is this African artist that has this completely different style. But everything shares a similar process of me being inspired by an everyday object and then using that as a medium for the actual work. From there, I start to beat myself up inside my head, which is part of my process. I’ll be flustered and stressed thinking about how to build the piece, trying to work through it. I hate my process sometimes because I go through this period of beating my head up, and then come out of that with the actual idea a couple of days later, and get it on paper. From there, I might go straight to building the sculpture and looking at materials, but there’s not always a sculpture.

I taught myself 3D modeling about five or six years ago because I was always fascinated with it. So then I can go into the program and actually build a sculpture in there, look at the sculpture, and then physically build it. Sometimes I’ll use large-scale machines, like beyond what my studio can hold.

It sounds like you live with the piece in your mind for a little bit before it becomes a material thing. So, where did the sneaker boxes come from? How did that become your signature medium to translate your work from concept to reality?

That started about 10 years ago. It’s just like the story of El Anatsui, whom I mentioned earlier. He makes tapestries out of bottle caps and is world-renowned, but he found them on the side of the road and was inspired when he saw a plastic bag on the street. My situation: I had a large number of sneakers and for no reason. Over a period of time, I was hustling in the streets and doing a bit of everything. I was making all this money and just spending a lot of it on kicks. My dedication to sneakers came and went, but when I left Seattle and came back to Chicago, I landed at this shop called Custom Kings which was pretty much like a one-stop shop for maker culture, music videos, etc. At the time, Virgil Abloh was running the shop, before he started working with Kanye. They had a lot of culture and a lot of influential people in hip-hop, fashion, and footwear at the shop, all of whom had a significant influence on me.

One day I was cleaning up my crib and had about 60 shoe boxes at the time, and I was exhausted from going through my kicks trying to figure out what to match up with what I was wearing. So I pushed the boxes into a pile in my living room, then I turned around to look at this pile of compressed boxes, and ideas sparked in my head. My first idea was to take the packaging and staple it to a wooden canvas board and then paint on top of it. So I gathered those items, went to the studio, and I remember throwing the boxes on the table. When I threw the boxes on the table, they kind of bulked up and formed this 3D head. I went to college for sculpting and other techniques, and I had seen this form in the packaging, so I really got into it from there. The first thing I built, at the end of 2009, was a lion. When I finished the archetype, people went nuts over that sculpture. Not just art collectors, but the sneaker community too. People started to show up to the studio and drop off boxes for me to keep doing my thing. From there, I just stopped everything I was doing besides my art.

Sneaker culture, and sneaker boxes, are a considerable part of your art. When did sneakers become so important to you?

I grew up in Chicago during the Michael Jordan heyday and was drawn to him first, to be honest. I looked up to him as a role model, and I had to have anything associated with MJ, like the AJ1s and the AJ3s. From that came my love for sneakers and the brand. If you talk to my dad about what I was like when I was young, he’ll tell you I was Nike or nothing. I was mesmerized by and loved the brand, and I loved that it was connected with this figure that I looked at as a basketball god. I also think the art, design, and details on Jordans are superior. It set the tone for everything that evolved into what we have now, including the professional vertical of sneaker art that I got into.

You mentioned that your first piece was a lion, and you have quite a few pieces with animals as subjects. Where do animals figure so prominently in your work?

Between my interest in sci-fi and alien movies, my aunt’s massive African mask collection, and comic books, I’ve developed cool ways of telling stories behind characters, animal archetypes, masks, or anything else. I wanted a way to tell my story but not have it be so literal. I also felt that these animals represented another form of me. I think my family dynamics and the importance of family, and lions representing pride, inspired me. I looked at the lion as an archetype for the power and what it represents as king of the jungle, but also what I admired about my family. I feel like the pride was something that I never had, but did subconsciously, and those things came into the mix. I also just love animals and beasts and those types of archetypes.

Christophe Roberts working in his studio // image courtesy of the artist

We’ve talked a lot about your inspirations and your work. But let’s take a step back: what does Art mean to you?

Art not only allows me to go into the inner depths of my mind and see how it works, but it’s also a way to understand someone’s narrative in a beautiful, visual way. When I’m looking at art, I like to pull some type of narrative from it or take inspiration from it. But art is also a release for me; it’s my psychologist. It’s a place for me to look at a lot of the things that are going on inside my head across all the different archetypes I work with. I feel like I have some dormant anger inside of me because I can really commit to working through some of those frustrations with art. Art has also contributed to my growth as a person and my understanding of the world. I can’t pinpoint what art has meant to me because it’s been everything: It’s been my parents, it’s been my psychologist, it’s been my lover. I’m married to it; I’ve fucked up relationships because of it. It’s everything.

Your work isn’t bound by any single definition or notion of genre. I imagine you end up with a diverse audience. So, who is your audience? Are they art people or sneaker people? Are they somewhere in between?

My audience is so interesting, man. When I first got into the fine art world, Brian Jungen, who does Native American art out of sneakers, was the only other person in that world that was doing something similar, and he was selling pieces at $20,000 – $30,000 or around there. My audience is definitely into sneaker culture and fine art. In the very beginning, though, like when shit was really popping, the sneakerheads held me down like no other. Also, what was going on at the very beginning is what ignited how things are going now for me.

But my audience is a combination between the sneaker community and the fine art community. It’s well balanced in that way, and I would say they are anywhere from like 18 to 45 years old. In terms of who’s buying the work now, the fine art world definitely helped me put my work at a certain level where I got into certain collections with certain families, and my work was not just looked at as a fad or something.

The art world has changed a great deal because developments like Instagram have taken out the curator, who was typically the middleman between you and the client. Now I can interact directly with the sneaker community and the fine art world at the same time and not even really have to fuck with art galleries at all. I can just sell the shit out of my gallery in Brooklyn or do one-off events or do one-off shows with galleries, but I don’t have to depend on them.

My audience is supportive of me, and I thrive off of that. But I would have to say it’s a balance between the sneaker community and the commercial community. For example, Nike is one of my biggest collectors. They, along with marketing agencies, buy a lot of pieces. There’s also the fine art collectors, the new collectors, those who have collected from galleries I’ve shown at, so it’s a melting pot. Yeah. Honestly, I wouldn’t be able to survive without that melting pot. I’ve been able really to grow from the fine art vertical and own it for the sneaker community and represent them.

It’s also interesting that your work and your audience come from different communities representing the art world and the commercial world. What is the difference between art and consumer products?

Art has a rawness that consumer products don’t have. Consumer products are manufactured and replicated at a pace that is hard for an artist to even keep up with, while art is more like a one-of-one.

For example, I built all my pieces by hand, but over time I started evolving as an artist and streamlining the process to keep up with the demand and immediate need that people have. I’m almost done with a product that will allow my consumers to build their own manza sculptures. When I think about the difference between art and consumer products, to create consumer products is like taking an artist’s work and manufacturing it 1000 times.

The difference is that people want the originals; they want the one-of-ones. They want the story and what I was going through when I made it because they’re following my life. This is the evolution of the work. It’s like Picasso when he went through a blue period and painted portraits of the women he was in love with. That is part of the story of the art and what art is all about. The narrative is so tied into the pieces, which is much different from a consumer product. Again, those products can have some meaning to them, but they are missing the texture and rawness that art has. To me, commercial products don’t have as much texture and rawness to it for it to be unique, like art. Art is inspiring. It changes the culture and the ways we think.

Second to last question: What does success look like for you? How will you know when you’ve made it?

Success is waking up in the morning, stopping by the coffee shop and grabbing a coffee, getting to my studio, and working all fucking day. That’s what I’ve always wanted. I’ve always wanted to have this and it doesn’t even sound like a lot. To me, it was just about being able to commit to my craft and not doing it for nobody but myself, my brand, and my legacy. So if I were to die right now, success is having enough books and art pieces around for my story to still be told and preserve that legacy for my family. Of course, I want to live forever, but I’m at a period in my life where I’ve gotten comfortable thinking about death, only because of the accomplishments that I have achieved, like the permanent collections I’m in.

I have a lot more to conquer. I’m not saying that I made it, but this is what success looked like for me a while ago, and now that I’ve acquired that, you know, the next level of success I’m after has changed as well. I feel like it comes in increments and that ceiling changes.

To wrap things up, then, what else should people know about you and your art?

This right here is a raw form of art. This isn’t something that I created to get in front of a brand. It’s just something that I stumbled upon while growing up in Chicago, and it’s evolved into something beautiful that I work at every day. I’ve got a lot of new stuff coming out, too. I’m doing a lot of different things in terms of materials and types of work; I’ve been working on this anime series about a post-apocalyptic world in the future, so I’ve been building out the characters for that. My studio has gone into a lot of other verticals besides what you see.

See more from Christophe Roberts and learn about more artists within the culture in “No Curator.”