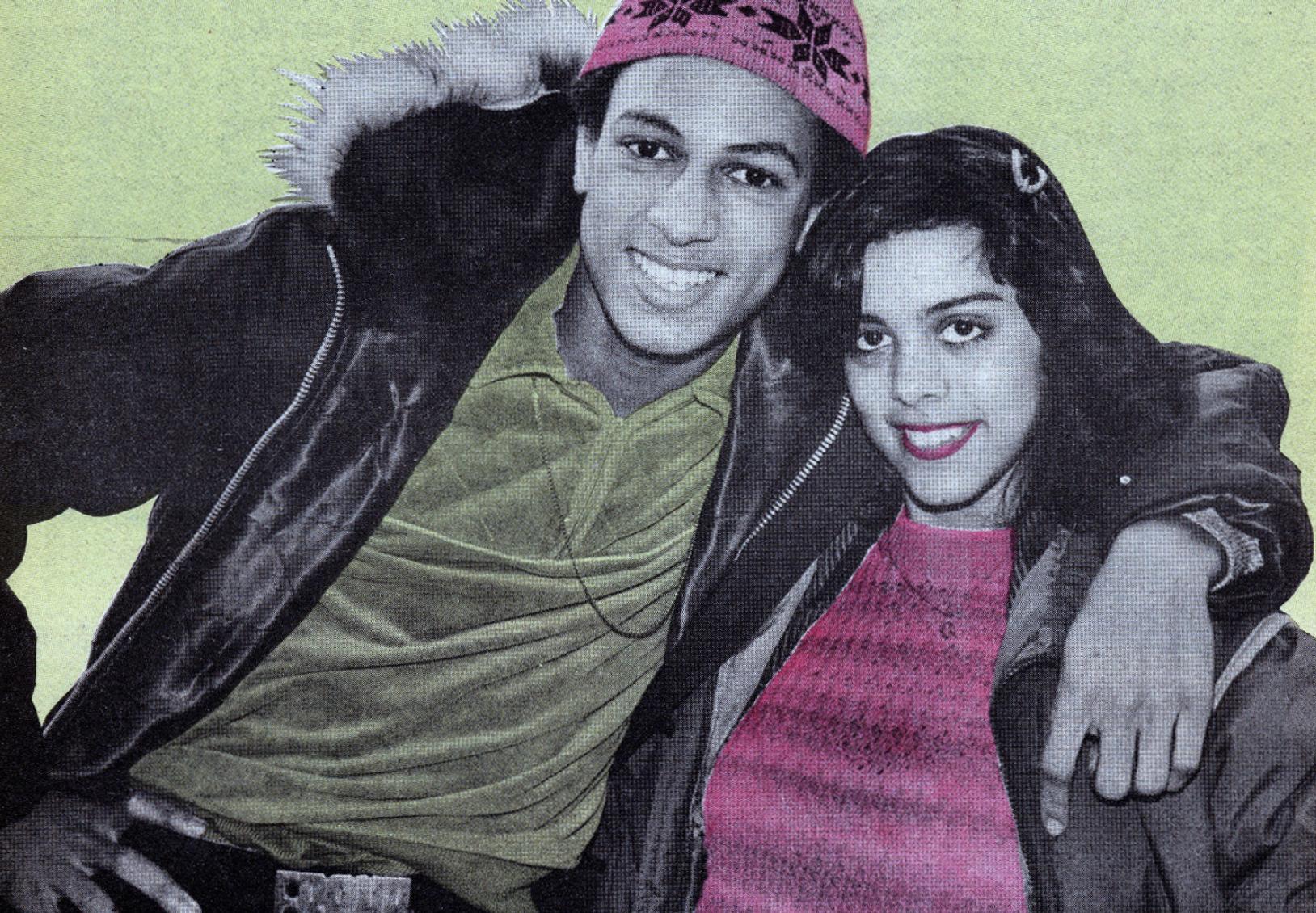

The “Ski Look,” January 1982 // East Village Eye

There’s a hell of a lot left to talk about when it comes to hip-hop. And we need to keep talking about hip-hop because of its titanic importance. Hip-hop is the most important American cultural creation since the end of World War II; it is the most influential cultural creation in the world since the 1950s. There is literally nothing that happens in contemporary American society, and most of the world, that hasn’t been reflected, refracted, or influenced by hip-hop in some way.

The impact is even more pronounced when we focus on the communities invested in and dedicated to the culture and products in which StockX exists. And that’s exactly what’s worth exploring: the ways in which hip-hop has shaped American culture and what we do here at StockX.

Since we’re in the middle of winter, it’s only appropriate that we start by examining hip-hop’s relationship with winter wear. From function to flex, hip-hop and winter wear have been connected from the start of the hip-hop nation.

Party Like it’s 1973

Since hip-hop culture coalesced in the Bronx in the early ’70s, it has spread all over the world, to all regions, countries, and climates. We recently made it through a Hot Girl Summer by way of Houston, but don’t forget that hip-hop came to us from the colder climes of New York. According to popular history, hip-hop began on August 11, 1973, at DJ Kool Herc’s “Back to School Party” in the rec room of his building at 1520 Sedgwick in the Bronx. August in New York is hot (think Do the Right Thing); no one was thinking about winter at Herc’s party; no one was thinking about much else but having a good time before the start of the school year.

Early hip-hop jams were decidedly homespun affairs held in apartment buildings and neighborhood community centers. The records, turntables, and speakers were cobbled together from family collections and stereo systems. These were teenaged spaces full of youthful fun and mild transgressions—more akin to self-conscious high school dances than slick nightclub nights. And the dress code reflected a combination of Delancey Street chic mixed with neighborhood style. It didn’t matter if you were a nascent DJ, MC, or packed on the dance floor, you dressed to flex.

Party flyer for DJ Kool Herc’s first party

Party flyer for DJ Kool Herc’s first party

Complicating this popular history is Afrika Bambaataa, the Zulu Nation founder and one of hip-hop’s godfathers, who argued that hip-hop’s birth was November 12, 1974. Bambaataa made this assertion because November marked the start of the “indoor jam season” when everyone had to move “indoors for about seven months . . . for the fall and winter seasons.” Before the park jams proliferated throughout the city during the summer, the first hip-hop heads got together inside in rec rooms and community centers, throughout the Bronx and beyond. Inside the jams, the people, the music, and the vibes were hot, but you had to brave the cold to get there first.

(L): Cold Crush Brothers at the Zulu Nation Anniversary Show (1981); (R): Audience at Cold Crush Brothers show (1981) // both photos from the Joe Conzo, Jr. photographs and ephemera, #8091. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Early hip-hop jams were events packed with kids from different neighborhoods and representing various aspects of nascent hip-hop culture: DJs, MCs, graffiti writers, and b-boys. Underpinning this flux of people and styles was competition. You had to come correct if you were going to make a name for yourself, your neighborhood, your crew. How do you do this if you’re coming from working-class communities with little disposable income? You flex with crazy, original style shot through with statement, aspirational brand pieces. Winter weather was no excuse for looking washed.

First There was Hip-Hop, Then There was “Ski”

Hip-hop has had a long love affair with winter wear. Winter wear and style—from the aspirational to the functional—has always overlapped with New York youth fashion and hip-hop culture. As early as the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, youth fashion and hip-hop culture deployed a variety of sports and technical gear as statements of self-expression. From the streets to the slopes, hip-hop has remixed and recontextualized winter wear for all seasons.

In a seminal series of articles, the January 1982 edition of the East Village Eye introduced breaking, graffiti, DJing, and MCing as a holistic cultural force. In this edition, Michael Holman—downtown scenester, musician, and early hip-hop impresario—became the first person to publish the term “hip-hop” in his interview with Afrika Bambaataa. These articles provided an important primer on the prominent hip-hop practitioners and the concatenated youth practices that form hip-hop

Front cover of the January 1982 edition of the “East Village Eye” // author’s archive

In this same issue, Holman also broke down hip-hop fashion history from the earliest Bronx crews to the contemporary trends of the early ‘80s. The big trend that Holman identified was ski wear. “I knew it [ski wear] was to be the look of winter ‘81,” Holman wrote, “but I didn’t expect the ski sensation to have such a broad influence on NY’s ethnic culture.” To get to the bottom of this new cultural phenomenon, Holman traveled uptown from the Lower Eastside to Kennedy High School on 225th Street in the Bronx, where he met up with legendary b-boys Crazy Legs and Frosty Freeze to see all the ski wear in situ.

Describing the scene, Holman said, “we saw ski pros and ski bunnies, icemen, snow queens and chilly dames; it was Aspen.” But what was most important was the vibe the kids were giving off in their ski wear: it was an “exact emulation of ski sportswear without the desire to ski.”

Michael Holman’s article, “YO-SKI,” from the January 1982 edition of the “East Village Eye” // author’s archive.

Moving from vogue to vocabulary, Holman traced the history of “Ski” in the names of MCs, DJs, b-boys, and graffiti writers to the TV show “Starsky and Hutch” (ABC, 1975-1979). The “y” is changed to an “i” and the connection between hip-hop and skiing is cemented, most famously by pioneer DJ Lovebug Starski. This was hip-hop appropriation at its purest: remixed and recontextualized for the sake of hip-hop culture, not for popular culture, and definitely not for ski culture.

The Golden Age and Winter Wear

As hip-hop continued to grow, the sounds and the styles changed while the connection to winter wear remained. In the Golden Age of Rap (the late ‘80s to the mid-‘90s), when boom-bap was the sound, groups like Public Enemy, Gang Starr, Erik B. and Rakim, and Boogie Down Productions ruled, and New York was the undisputed center of the hip-hop nation. This was also a golden age for winter wear, no matter how hot it was outside at the park or inside the jam. The uniform of choice during this period was clear: oversized everything and timbs. This type of generalist fit would get you through any weather or situation in the urban jungle. But just as hip-hop was expanding to include a broader range of sounds and styles during this era, so too did variation seep into hip-hop’s sartorial palette.

Biggie (L) and Gang Starr (R) rocking timbs in the spring and fall, respectively.

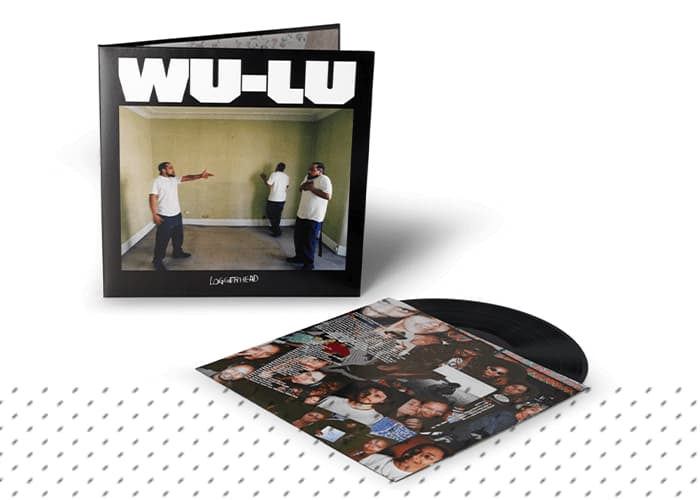

Perhaps the most famous meeting of hip-hop and winter wear comes courtesy of Raekwon the Chef and the Wu-Tang Clan. In 1994, the Wu-Tang Clan released their video for their song, “Can It Be All So Simple.” The video went on to transform the relationship between Polo Ralph Lauren, hip-hop, and New York’s ‘Lo Life streetwear scene from a very specific, local culture, to a mainstream phenomenon. This mid-‘90s went beyond aspirational fashion choices; this was a moment when Polo and hip-hop appeared collaborative: fashion and music made for each other.

Raekwon rocking Snow Beach from Wu-Tang Clan’s “Can It Be All So Simple” (1994)

Polo Sport Ralph Lauren introduced the Snow Beach collection in 1993, adapting emerging snowboarding culture and attitude into the brand. The result was a collection leaning heavy on color-blocking and the inclusion of graphics on technical pieces. It was bright, it was bold, and it captivated new audiences beyond the hardcore ‘Lo heads to pay attention. As Polo worked on updating its look and brand identity, Raekwon epitomized Polo and the fashion world’s increasing embrace and appropriation of urban culture, style, and music.

When Rae first appears in the video, he’s wearing a Polo Sport Ralph Lauren Snow Beach pullover jacket. The simple blue and gold color-blocking and the bold red graphic lettering, paired with Rae’s charismatic presence cemented Snow Beach as one the most iconic and sought after collections in hip-hop history, quickly making it the epitome of streetwear cool. Since the 1994 video, Snow Beach, and Snow Beach-inspired apparel has remained a constant design touchstone for the last 25 years.

The enduring popularity of Snow Beach led Polo to re-release the “Snow Beach” line in January of 2018. The fact that Polo revisited this collection at all is entirely thanks to Raekwon and the Wu-Tang Clan. However, Polo failed to give props to Rae and hip-hop for keeping the Snow Beach faith. “They should have called me,” Raekwon said in an interview shortly after the relaunch of the collection in 2018. Reflecting on his outsized importance in making the line iconic, he remarked, “I felt a little bit insulted that I didn’t get a personal call.”

But technical pieces designed for winter weather were an increasingly common part of hip-hop and hip-hop fashion. Before the near-ubiquity of ski goggles as a fashion statement in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, winter wear was increasingly functional and fashionable, no longer only about the flex. By the mid-’90s, staying warm and looking dope on the block wasn’t enough, rappers needed clothing that performed on the slopes, too.

Naughty by Nature’s 1995 video “Feel Me Flow” takes hip-hop to the mountaintop resort. The first half of the video features the group posted up outside in the city’s summer heat. The second half of the video cuts to a ski resort with Treach, Vin Rock, and DJ Kay Gee on snowboards carving their way down the slopes. The video’s message is direct: Naughty by Nature’s flow is so hot, it’ll keep you cool no matter the temperature. However, the video’s message only makes sense by understanding that hip-hop has now become solidly middle-class. This is a seminal moment in hip-hop and popular culture. Through winter wear and ski culture, this video signals that joining the ranks of the middle-class represents hip-hop’s upward mobility. From the urban core to the suburban strip malls, hip-hop has arrived.

From Naughty by Nature’s “Feel Me Flow” video (1995)

In fact, it makes sense that Naughty by Nature was one of the first big hip-hop acts to move the culture’s embrace of winter wear from fashion to function. By 1995, Naughty by Nature was huge due to their crossover hits including “O.P.P.,” “Hip Hop Hooray,” and “Groove Thang.” In 1996, Naughty by Nature won the first-ever “Best Hip-Hop Album” Grammy award. The group was successful precisely because they balanced hip-hop authenticity with pop appeal. From a fashion and cultural perspective, Treach and the gang best illustrate hip-hop’s socioeconomic pivot from Rae’s aspirational street-life winter wear flex of the early ’90s to the elite vacations of transcendent hip-hop stars such as Diddy, Kanye, and Drake in the 2010s.

The ‘90s, Shiny Suits, Goggle Fashion, and Beyond

Big Pun’s “Capital Punishment” album cover might be the high-water mark of the combination of ski goggles as hip-hop fashion accessory and display of pure lyrical acumen. Yes, Pun and his goggles look outdated today, but “Capital Punishment” still stands as one of the greatest debut hip-hop albums of all time. And of course, Ma$e and Diddy, with the direction of Hype Williams, single-handedly kicked-off the “Shiny Suit Era” of hip-hop with the video for “Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems,” complete with goggles. The late ‘90s and early 2000s were also the moment when hip-hop culture became the ascendant American cultural force. This was an era of multi-million dollar video shoots and hip-hop’s emergence as a billion-dollar industry.

From the “Mo Money, Mo Problems” video (1997)

By the mid-2000s, hip-hop was flush with money and cultural capital, and a newer generation was ready to flex. Enter swag rap, a subgenre compulsively dedicated to the presentation and the display of wealth and excess. Amorphous in sound, geography, and practitioner, swag rap emerged as a brand new floating signifier and cultural shorthand for hip-hop’s rising affluence than tied to traditional hip-hop referents like sound, locale, or crew. Swag rap’s sole purpose was to deliver bangers to soundtrack this era of conspicuous consumption. Everyone from Kanye, Lil B, Odd Future, Migos, even Kreayshawn have dabbled in swag rap. Typifying this era is Soulja Boy’s Gucci ski goggles in The Ranger$’s “Touch Down” video from 2011. Soulja Boy is perfect in his swag excess.

Soulja Boy in The Ranger$’s ”Touch Down” video (2011)

In 2016, Tyler, The Creator and Frank Ocean released a photo in homage to Soulja Boy and hip-hop’s affinity for ski goggles as a fashion accessory

Still Powder Flexing

Almost 40 years after ski and winter wear were incorporated into hip-hop culture the winter fits are still crispy. Winter wear and hip-hop are still hot.

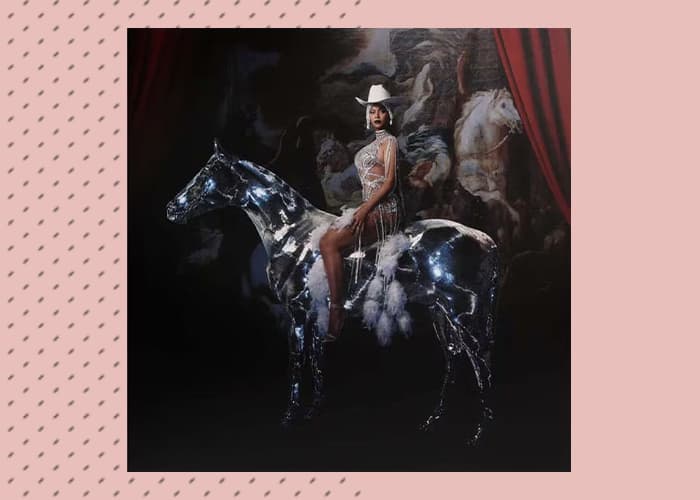

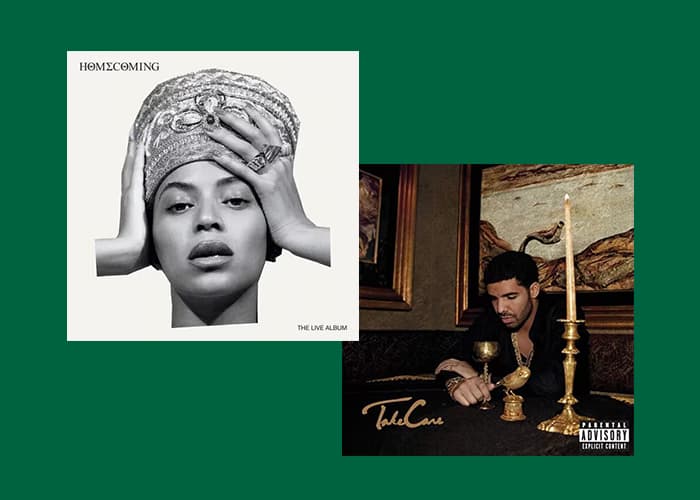

Drake’s latest video, “War,” represents a visual celebration of all types of cold-weather gear and hip-hop. From the opening, out-of-focus frames of snowfall to the final shot of Drake in front of a bonfire, alone in the cold. Everyone in the video is wearing some combination of Canada Goose, Nike, North Face, Moncler, and of course, OVO. The video also shows Drake and company enjoying nighttime snowmobiles, skiing, and snowboarding. The entire video is a celebration of hip-hop and cold weather sports. “War” represents the journey from fashion appropriation in the early ’80s, to the full-on hip-hop winter fashion flex of today. All of the brands and items worn in the video cost stacks on stacks on stacks, pushing swag rap into a whole new tax bracket.

From Drake’s “War” video (2019)

Flipping the initial appropriation of winter and ski wear by hip-hop culture, hip-hop and street-inspired fashion continue to inform winter wear and winter sports pieces. Blending the relationship between skate culture, snowboarding, streetwear, and hip-hop, FTP collaborated with DC Shoes for a line of snowboards and snowboarding apparel during the FW 2019 season.

Finally, no examination of hip-hop, winter wear, and fashion would be complete without discussing Supreme and The North Face. Since 2007, the two brands have collaborated on everything from jackets and t-shirts to bags, hats, and other accessories, with stunning reimaginings of the classic Nuptse coat. Everyone from Playboi Carti, Drake, A$AP Rocky, and Travis Scott have rocked items from this ongoing and historic collab, firmly cementing the enduring link between hip-hop culture and winter fashion.

The connection between winter wear and hip-hop has been here since the culture’s Bronx beginnings. Although the money, the stakes, and status have dramatically changed, Drake’s video makes clear that hip-hop’s essential spirit of getting together with friends and having a party remains the same. As long as we still have hip-hop and we still have winter—you never know with climate change—hip-hop’s love affair with cold-weather fits will be here to stay.